The Home of

Micka Electric Company

General Electric Appliances

Maytag Washers

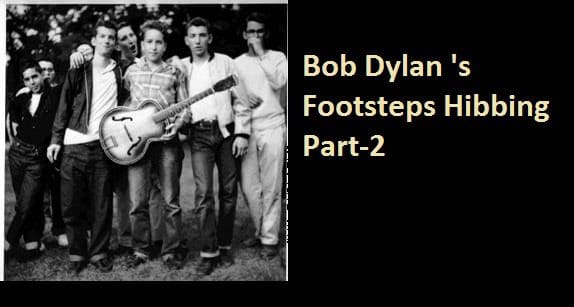

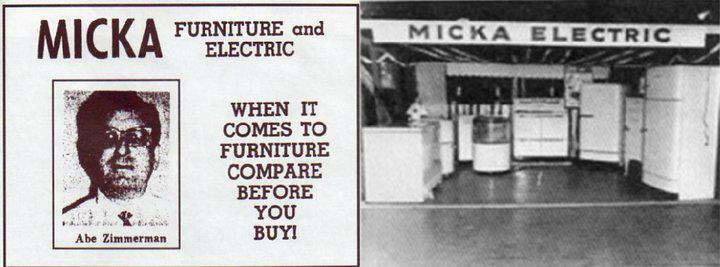

“Down that street, Fifth Avenue, is where Bob’s uncle’s shop is. Zimmerman’s Furniture and Electric. They’re finally going out of business, after almost twenty-five years. Bob’s father used to make him do odd jobs around the shop. He and this other fellow sometimes would have to go out on a truck and repossess stuff. I think that’s where Bob first started feeling sorry for poor people. These miners would come to town, find a house, buy furniture on the credit their job promised them, and then got laid off when a mind shut down. Then Bob and his friend would have to go over and take away all the stuff bought from Zimmerman’s. Load it onto the truck and just leave. Bob hated that; used to dread it worse than anything.” — Echo Helstrom

1925 5th Avenue East, Hibbing, MN 55746

In about 1920 Edward Micka started Micka Electric. In 1944, Ed Micka died and Maurice and Paul Zimmerman, who had been working for him, purchased Micka Electric. Bob’s father, Abe, joined the company in 1947 and became the secretary/treasurer. As a teen, Bob worked in the store, making deliveries among other tasks.

“He used to work for me. He was strong. I mean he could hold up his end of a refrigerator as well as kids twice his size, football players. I used to make him go out to the poor sections, knowing he couldn’t collect money from those people. I just wanted to show him another side of life. He’d come back and say, ‘Dad, those people haven’t got any money.’ And I’d say, ‘Some of those people out there make as much money as I do, Bobby. They just don’t know how to manage it.’” – Abe Zimmerman (Scaduto, p. 16)

“The Zimmermans really leaned over backwards for a lot of people; they let it go right to the end.” [Abe would rack his conscience over an outstanding account until it was impossible for him to carry it any longer.] “A lot of the time Abe would have Bobby go with me when I went to repossess stuff. He’d sit in the truck and smoke until it was time to carry out whatever it was we were taking back. It really hurt him to have to do this, but Abe left us no other choice.” – Benny Orlando (the store’s service manager for 18 years) (Spitz, p. 61)

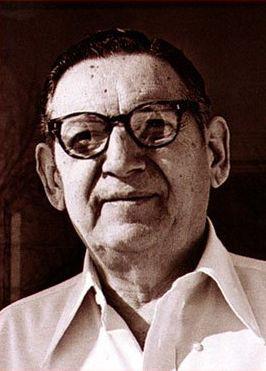

Paul Zimmerman (21 November 1905 – 17 March 1981)

Zigman/Zigmond Zimmerman 1876-1936 Odessa Ukraine arrived USA 1907 salesman shoe store dry goods

Anna (Greenstein / Kyrgyz?) Zimmerman 1879 (married Zigmond 1898) Kars Turkey? Odessa Ukraine arrived USA 1910

Maurice Zimmerman 1901-1981 Odessa Ukraine arrived USA 1910

Marian (Minnie) Zimmerman 1903-1996 Odessa Ukraine arrived USA 1910

Paul Zimmerman 1905 Odessa Ukraine arrived USA 1910 salesman Woolin Company then shop

Jack Zimmerman 1909 Odessa Ukraine arrived USA 1910 salesman grocery store.

Abe Zimmerman 1911-1968 born in Minnesota oil company (accountant) then shop

Max Zimmerman 1914-1996 born in Minnesota newspaper then shop

Beatty (Stone) Zimmerman 1915-2000

Abram H. Zimmerman, Bob’s father, was born in America, in Duluth, Minnesota, on October 19, 1911, into a family of four other children. If you believe the 1920 census details, Abe was the first of the family born in the USA. It is more reasonable to believe the 1930 census, which says that Jack/Jake was born in the USA a year ahead of Abe.

Abe’s father — Bob’s paternal grandfather — is Zigman Zimmerman; his Hebrew name is Zisel. ‘I don’t know how they got a German name,’ said Dylan in the 1978 Playboy interview. Zigman was born in the thrusting Russian port of Odessa on Christmas Day 1875, and grew up in an atmosphere of active, vicious anti-Semitism. He seems to have run a shoe-making business before he fled Tsar Nicholas II’s pogroms in 1906. His brother Wolfe not only stayed behind but became a soldier in the Russian army.

Zigman arrived into the US in 1907, through Ellis Island to New York City, like so many others. From there he moved north-west until he arrived in Duluth. He worked as a peddler and sent for his family soon afterwards: by 1910 they had arrived. His wife Anna, formerly Chana Greenstein, born in Odessa on March 16, 1878, had given birth to three children before their emigration: Maurice, aged eight on arrival; Minnie, aged six; and Paul, four. They squeezed into a small apartment at 221/2 West 1st Street, where we presume the fourth child, Jake, was born (though the 1930 census says he was born in Wisconsin). Either way, before the next brother, Max, came along in 1914, the Zimmermans had moved to a house: 221 Lake Avenue North, Duluth. It is the only one of the houses Bob’s father lived in as a child and as a young adult that does not still exist.

Zigman was still a peddler when Abe was born, but by 1917, Zigman, now styling himself Zigmond H. Zimmerman, was a ‘solicitor’ working for the Prudential Life Insurance Co. He had obtained his naturalization papers in 1916, but when the USA entered the Great War in 1918, the Zimmermans were forced to register as aliens. His wife Anna told the registrar she was a dressmaker, and that she spoke ‘a little English’. Zigman could speak it but not read it. By 1920 he was a dry goods salesman; later that decade he opened his shoe store but it failed, and by 1930 he was a salesman in someone else’s. All the same, in 1925 they moved again, to a two-story house at 725 East 3rd Street.

By 1930 the oldest children, Maurice and Minnie had left home, Maurice first working on railway equipment repairs and then as a railway ticket inspector, while Minnie worked as a typist at the Duluth Herald newspaper. Still living at home, 24-year-old Paul had become packer, clerk and then salesman for the Manhattan Woolen Mills. Abe, who by the age of seven had been shining shoes and delivering newspapers, had graduated from the Central High School in 1929, was now 18 and working for the Standard Oil company, first as messenger boy and then as clerk. As Bob commented in 1978: ‘. . . my father never had time to go to college.’ When Abe, aged 22, married 18-year-old Beatty, whom he’d met on one of her weekend trips to Duluth, on June 10, 1934 at her parents’ house in Hibbing, his older brother Paul was best man. They honeymooned in Chicago and then came back to live in Duluth, with Abe’s mother and the three youngest brothers at 402 East 5th Street. Abe’s father, Zigman, had moved out and had an apartment in the Kinsley Apartments on West 1st Street. On July 6, 1936, he died of a heart attack in the street on 2nd Avenue West, in a heat wave, at the age of 60.

Abe duly became a senior manager at Standard Oil, and ran the company union; he and Beatty moved house several more times, finally escaping Abe’s siblings by moving into the upstairs of a duplex at 519 3rd Avenue East, high up on the hillside overlooking the port and Lake Superior. Their first child, Robert Allen Zimmerman, was born at the nearby St. Mary’s Hospital on May 24, 1941, weighing in at 7 lb 13 oz: ‘about as big as a good-sized lake trout,’ writes Dave Engel, in Just Like Bob Zimmerman’s Blues—Dylan in Minnesota. Robert Allen’s Hebrew name is Shabtai Zisel ben Avraham.

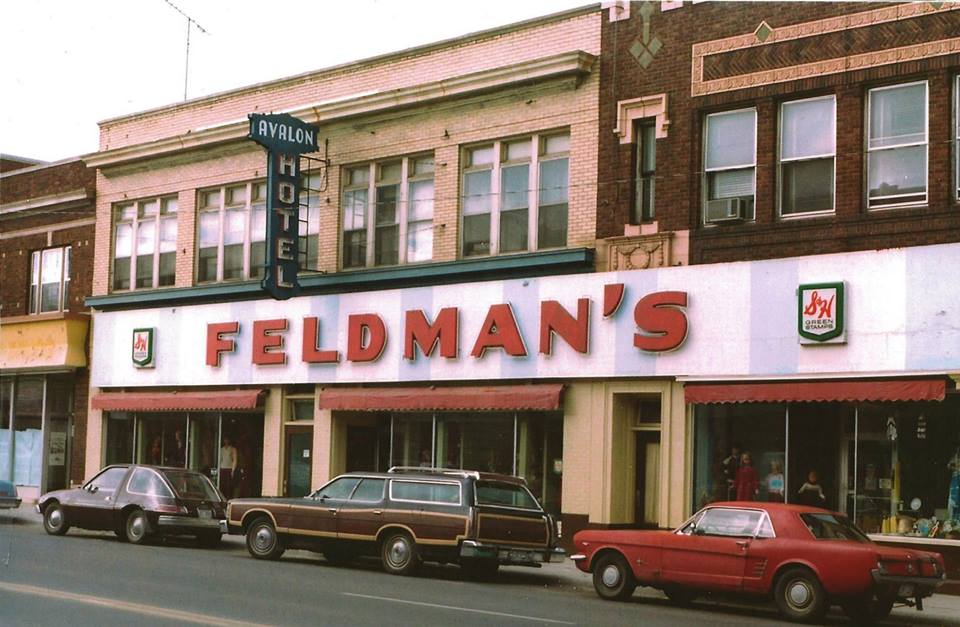

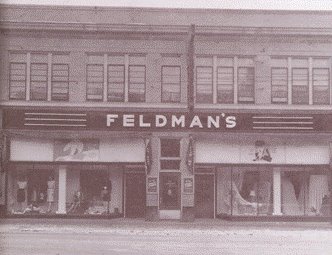

In 1947 the family moved to Hibbing, where Abe’s brothers Maurice and Paul had set up [i.e. had bought] Micka Electric Co. the year Bob was born. Abe became an appliance salesman. When Bob’s little brother David was a bit older, Beatty started working as a clerk at Feldman’s clothing shop in the main street, Howard Street.

Abe contracted polio and suffered its debilitating physical consequences all through Bob’s childhood. ‘My father,’ Dylan told the French paper L’Expresse in 1978, ‘was a very active man, but he was stricken very early by an attack of polio. The illness put an end to all his dreams, I believe. He could hardly walk . . .’ But others reported that he walked with a slight limp, not always noticeable. His mother, Anna, who had also moved to Hibbing, and lived for some years with Bob’s Uncle Maurice, moved into a nursing home in St. Paul and died there of arteriosclerosis on April 20, 1955. She had outlived her husband by almost 20 years.

Her death certificate, with the information supplied by Uncle Maurice, confirmed that she’d been born in Odessa. Dylan contradicts this, writing in Chronicles Volume One of visiting her when she still lived in Duluth: she ‘had only one leg and had been a seamstress. She was a dark lady, smoked a pipe. . . . [Her] voice possessed a haunting accent— face always set in a half-despairing expression. . . . She’d come to America from Odessa. . . . [but] Originally she’d come from Turkey, sailed from Trabzon, a port town, across the Black Sea. . . . Her family was from Kagizman, a town in Turkey near the Armenian border, and the family name had been Kirghiz. My grandfather’s parents had also come from that area. . . . My grandmother’s ancestors had been from Constantinople.’

Abe Zimmerman had a heart attack in summer 1966. On June 5, 1968 he died of a second heart attack. He was buried in Duluth.

Gray, Michael. The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. New York: Continuum, 2006, 0826469337, page 729f.

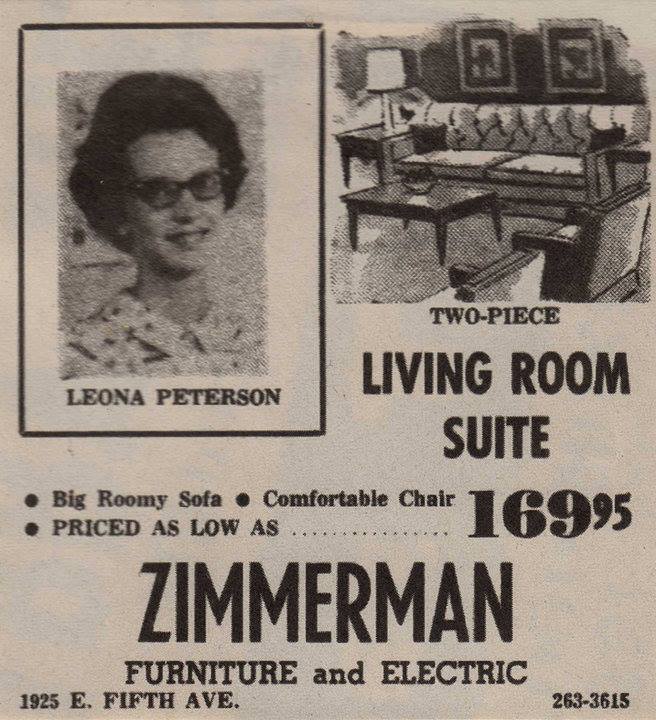

Bob Zimmerman’s Bar Mitzvah (בר מצוה) celebration at the age of 13 was at the Androy Hotel, 502 East Howard Street, Saturday 12 June 1954 (not Wednesday 22 May) with 400 guests. This was large for a Bar Mitzvah in Hibbing.

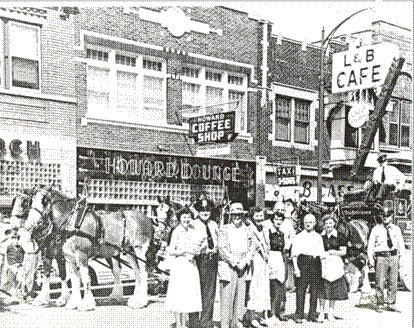

Bob had prepared for his Torah and Haftorah readings with Reuben Maier, an Orthodox rabbi from Brooklyn. (He was close to Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson a Hasidic rabbi and the seventh and last Rebbe of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement.) Bob and Reuben Maier studied in an apartment at 419 East Howard, right above the L&B Café, which had the best jukebox in town. The rabbi’s arrival in Hibbing was, according to a 1985 interview with Spin magazine, serendipitous.

“[Hibbing] didn’t have a rabbi,” Bob recalls. “When it was time for me to be bar mitzvahed [sic], suddenly a rabbi showed up under strange circumstances for only a year. He and his wife got off the bus in the middle of winter. He was an old man from Brooklyn who had a white beard and wore a black hat and black clothes. They put him upstairs of the café, which was the local hangout. It was a rock ‘n’ roll café where I used to hang out too. I used to go up there every day to learn this stuff, either after school or after dinner. After studying with him an hour or so, I’d come down and boogie. The rabbi taught me what I had to learn and after he conducted the Bar Mitzvah, he just disappeared…. I never saw him again…. He came and went like a ghost.”

In the same interview, Bob went on to say that he believed Rabbi Maier was forced out of the community because he was Orthodox, and too different from the more assimilated Jews of Hibbing. “Jews separate themselves like that. Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, as if God calls them that. Christians too. Baptists… Methodists, Calvinists. God has no respect for a person’s title. He don’t care what you call yourself.”

The tone of his recollection may give a hint of what it was like to be a Jew in a town dominated by descendants of the great Scandinavian immigration about whom Garrison Keillor, that other American poet from Minnesota, so fondly spins tales. A teacher at Hibbing High told biographer Robert Shelton that while many barriers had been razed, some remained. “In Hibbing, the Finns hated the Bohemians and the Bohemians hated the Finns. Nearly everyone hated the Jews.” According to Shelton, one classmate said, “The kids used to tease Bob, sometimes. They would call him Bobby Zennerman because it was so difficult to pronounce Zimmerman. He didn’t like that…. His feelings could be hurt easily. Later in high school he wasn’t so well liked, mostly because he stayed to himself so much.”

“All I did was write and sing…dissolve myself into situations where I was invisible,” Dylan said of his teenage years, when he hid away in his family’s attached garage with rock bands called The Shadow Blasters and The Golden Chords. Shelton connects this need for invisibility to the struggles of what he called alien assimilation. “The thirty or forty Jewish families of Hibbing still had to huddle together against the cold. Abe, who loved to play golf, couldn’t belong to the Mesaba Country Club.

East Howard Street with the Androy Hotel on the left.

Note the serious radio mast, upper left of the photograph. WMFG had studios in the Androy Hotel. In June 1942 WMFG dropped CBS and joined the NBC Radio Network. It remained with NBC until the early 1960s. By 1962 it was an independent station.

https://

The Androy Hotel, downtown Hibbing, Minnesota opened June 29, 1921. The name Androy came from the first names of two of the owners – Andrew Doran and Roy Quigley. Built and designed by the Oliver Mining Company, closed in 1977 and restored in 1994, it was placed on the National Register of Historic Buildings on 13 June 1985. The Androy apartments are open to people ages 55 and older and on a limited income. The apartments are modern and spacious and the building offers many opportunities for the residents to get together

Feldman’s Department Store, 405 East Howard Street, Hibbing, MN 55746

Nancy Peterson (she once competed against Bob Zimmerman at a talent show and beat him) worked with Beatty Zimmerman. “She recalls the day in ‘62 or ‘63 when the owner made this announcement: “This is R. W. Feldman. We have a celebrity in woman’s wear—Mr. Bob Die-lynn.”” Star Tribune, September 25, 2005, p. F8

Herman Feldman founded the store, his son Randy made the announcement.

Feldman’s Department Store 1925-1994.

Stone’s Clothing, 103 East Howard Street, Hibbing, MN 55746, at the southeast corner of 1st Avenue and East Howard Street. It was run by Bob’s grandmother Florence and his uncle Lewis. Lewis retired in 1967. It became the China Buffet, pictured here in 2010.

Ben Stone had met Florence Edelstein in Hibbing and they married in 1911 and set up an earlier store at Stevenson Location, twelve miles west of Hibbing, supplying clothing to iron ore miners’ families. When that mine was used up in 1937, they opened this store in downtown Hibbing instead. The store building was formerly owned by Joseph Mrkonich. After Ben died Florence lived in the Zimmerman house when Bob and David were growing up. Florence is the grandmother much praised in Chronicles Volume One.

“In 1995 in an Italian restaurant on New York City’s East Side two sisters were dining: Irene and Beatrice.

“But everyone calls me ‘Beatty,’” said the sister wearing the more elaborate necklace. Irene wore a double strand of white pearls.

It wasn’t until midway through our meal that “Beatty” revealed she was the former Beatrice Zimmerman, widow of Abe Zimmerman and mother of Robert Allen Zimmerman – otherwise known as Bob Dylan.

We didn’t talk about Dylan, though. Beatty was far more excited about discussing her talented grandsons Jakob and Seth, and both sisters were more interested in talking about their own lives: their grandfather’s chain of movie theaters, the clothing store in Hibbing, Minnesota, owned by their parents Florence and Ben (“The customers were mostly miners and their families, so it wasn’t fancy,” Beatty said) and how Beatrice had been widowed twice, first by Abe, who died of a heart attack in 1968, and Joe Rutman, who died in 1985.” — Charles Ferruzza

https://www.pitch.com/plog/

Alice School, 2300 2nd Avenue East, for grade one. It had a residence for teachers on its top floor. In 1979 it was torn down to become a parking lot, with part of the land used for a playground.

Grade

First 1947-1948 6

Second 1948-1949 7

Third 1949-1950 8

Fourth 1950-1951 9

Fifth 1951-1952 10

Sixth 1952-1953 11

Seventh 1953-1954 12

Eighth 1954-1955 13

Ninth 1955-1956 14

Tenth 1956-1957 15

Eleventh 1957-1958 16

Twelfth 1958-1959 17

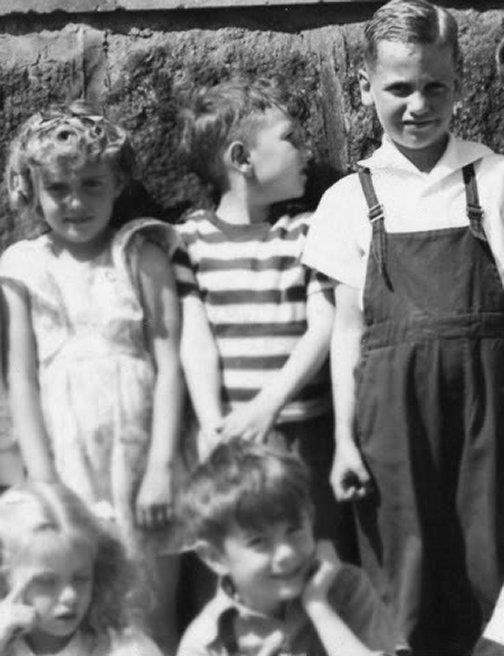

Bob Zimmerman in grade one at Alice School.

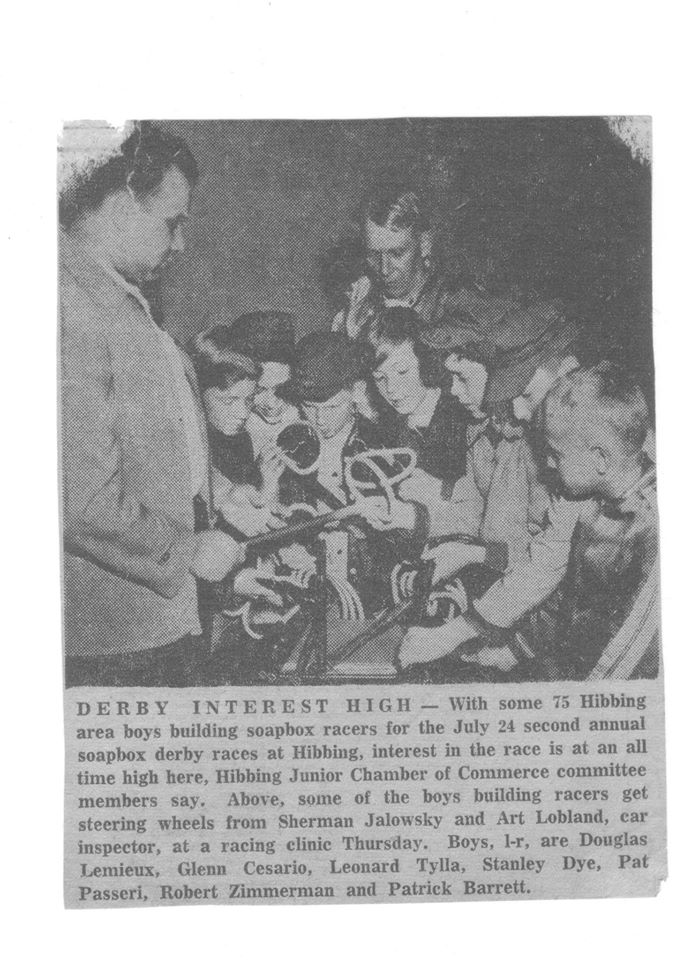

(circa) 1951? Racing Clinic for Hibbing Junior Chamber of Commerce

Prospective soapbox derby racer, Robert Zimmerman (2nd on right) wearing a billed-cap, lays hands on a steering wheel for his derby car. Did the racer get built? Did he race it? Is this the earliest known photograph of Bob in a hat?

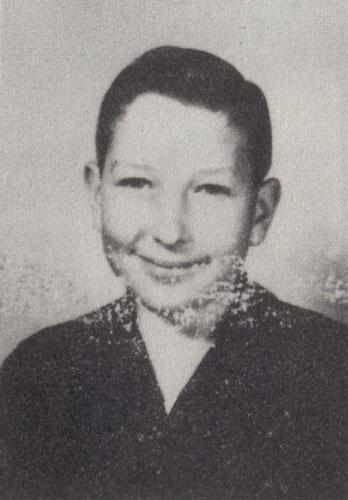

Bob Zimmerman 1952.

Bob Zimmerman, 12 years old, 6th grade, Washington School, 1953.

Or is it? Bob Zimmerman had Kindergarten in Duluth at the Nettleton Elementary School— 108 East 6th Street, Duluth, MN 55805 (1st Avenue East and Sixth Street). Then in Hibbing he attended Grade 1 at the Alice School and then Grade 2-12 at Hibbing High School. So the published sources which say this is Washington School are wrong.

Unusually Hibbing High School had Kindergarten to Grade 12 classes. The graduating class of 1962 was the last to have people attend all grades from Kindergarten to Grade 12. So from 1950 it was being phased out. — Sue Kanga Chaffee

Usually people called the school Hibbing High School for all grades, occasionally it was called Hibbing High Junior High [sic] and in conversation The Junior High.

Miss John’s 5th Grade Class 1952-1953:

Back row: Nancy Annes, David Rian, Bonnie Marinac, Shirley Zubich, Bill Marinac, Peggy Teske, Judy Hennessey

Front row: Griffith Thomas, Bob Zimmerman

The class was split up into three parts and made, decorated and played their rhythm objects. Circulating tapes?

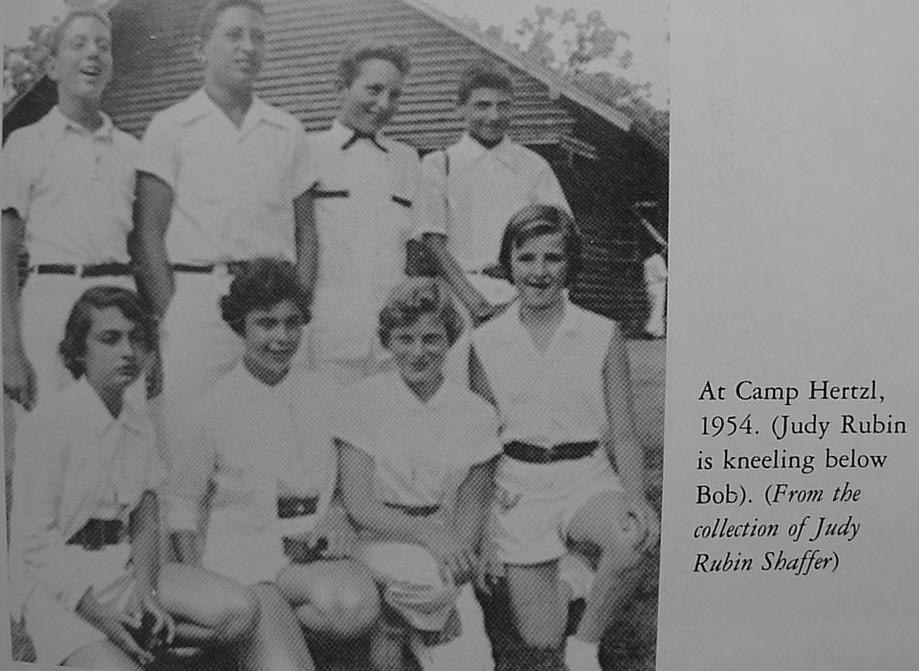

Bob Zimmerman and Judy Rubin at Camp Herzl, 1954.

https://

In its first brochure, Herzl Camp’s aim was “to bring a child closer to Jewish life and the Jewish people… to prepare the child to absorb the content and values of modern Palestine… to enlist the child’s interest and help in building of the Jewish national homeland.” In its first year, camp sessions were offered for children ages 12 and above. From the beginning, athletics, waterfront activities, recreation, music, dancing, cultural and creative events were all components of the Herzl experience.

The site on Devil’s Lake in Webster, Wisconsin had The Log Cabin Inn, ironically a “gentiles only” establishment, which became the home of Herzl Camp. The farmhouse was converted into a dining hall and kitchen. One of the larger fishing cabins became an activities building and a minimum of additional plumbing was added to make the site accessible to campers.

368 miles southeast of Hibbing almost as far as Madison, Wisconsin.

“Once there was Judy And she said Hi to me When no one else Could take the Time…But she broke me Up When she didn’t Write back and I died for a year – Seela And then there was Ione Who wore a Ring on her Left hand…my mind went Insane Every time I saw her – Seela Then there was Carol Who had tits Like headlights On a fire engine And a face like Helen … she’d rape my feelings … Then there was Barbara Her parents liked me And I liked them But I loved Barbara more…Then came another Judy She had a long Pony Tail And wanted Some day To be an Actress … Now there’s Judy again And my Circe starts Over … I don’t fit in anymore I’m Lost And my trouble is I know it”

Interesting that our hero, rebel rude boy, is the only one with a white shirt that does not conform to the camp rules…

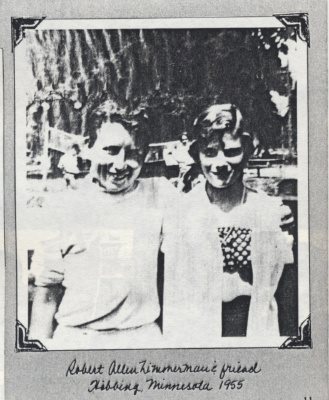

Bob Zimmerman 1955

Bob Zimmerman, Camp Herzl, 1956.

Bob Zimmerman 1956.

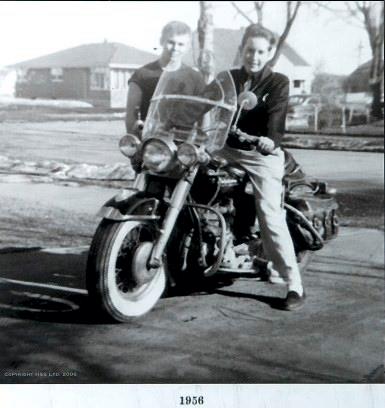

Bob Zimmerman with Dale Boutang “the best rider in Hibbing, a cowboy on wheels and a seasoned weight-lifter” and Dale Boutang’s Harley 74, 1956.

Photograph taken by Beatty Zimmerman, Bob’s mother. (This photograph is seen often on the Internet with the 1956 removed and a modern large 1957 added.)

“Waiting in the house was Raatsi on the bed/’I’m gonna pin Boutang’s arm,’ Melvin, then said/A noise outside! and Raatsi’s face had gleam/Ah ha, it was Dale coming on his machine/Raatsi came to the door and opened it wide/Dale Boutang then stepped inside/Roll up that sleeve and let’s get to work,’/Said Melvin Raatsi with a great big smirk/’I’m gonna arm-wrestle you to death said Mel the boy/’Shut up,’ said Boutang,’ I’ll take care of you like a little toy…”

“We’d pull into the Hibbing Rootbeer stand on Bob’s motorcycle when the weather was warm. One time, just outside my house on the old service road, he tried to teach me to ride it. He told me all about the controls, started it up and set me on board. Only trouble was my feet weren’t long enough to reach the ground. But I didn’t realize that until I’d already taken off. I made about twenty yards in first gear and thought I’d better practice stopping before I went any further, so I tried to put on the brakes; but something went wrong and the engine started revving and I hit a post or a tree and went head over heels. The motorcycle fell over and the rear wheel went crazy with sparks flying and gravel…Bob stood there with his mouth open and his eyes real big, not believing it.” — Echo Helstrom

Photograph courtesy of Leroy Hoikkala and Sharon Ness. This photograph was taken by Beatty Zimmerman in 1956 in front of Bob’s home. The photograph was a part of Tangled up in Ore a Bob Dylan exhibition at Ironworld. — t052008 — Clint Austin — austinIRON0522c3.

1956.

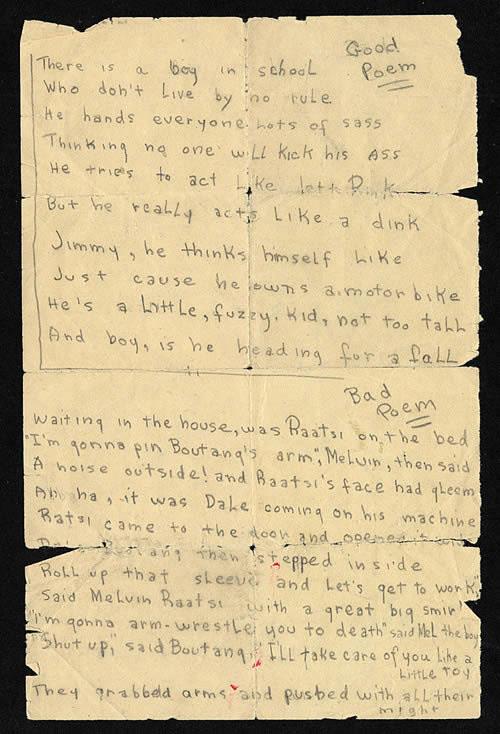

“There is a boy in school/Who don’t live by no rule/He hands everyone lots of sass/Thinking no one will kick his ass/He tries to act like Lett Rink/But he really acts like a dink/Jimmy, he thinks himself like/Just cause he owns a motor bike/He’s a little, fuzzy, kid, not too tall/And boy, is he heading for a fall.”

Jimmy is, of course, James Dean! He rode a 1955 Triumph T-110 650cc motorcycle and was in the films Rebel Without a Cause (1955), East of Eden (1955) and Giant (1956).

Sold for $12,760.00 by Robert Edward Auctions, Watchung, NJ 07069.

https://www.angelfire.com/

https://www.angelfire.com/

His parents, Mr. and Mrs. Abe Zimmerman of Hibbing, say whatever credit is due is his alone. “My son is a corporation and his public image is strictly an act,” says his father. He’s had no musical training to speak of – at least, his parents don’t speak of it. But they recall that he was always fond of poetry and started writing verses, which they have saved, when he was only eight.

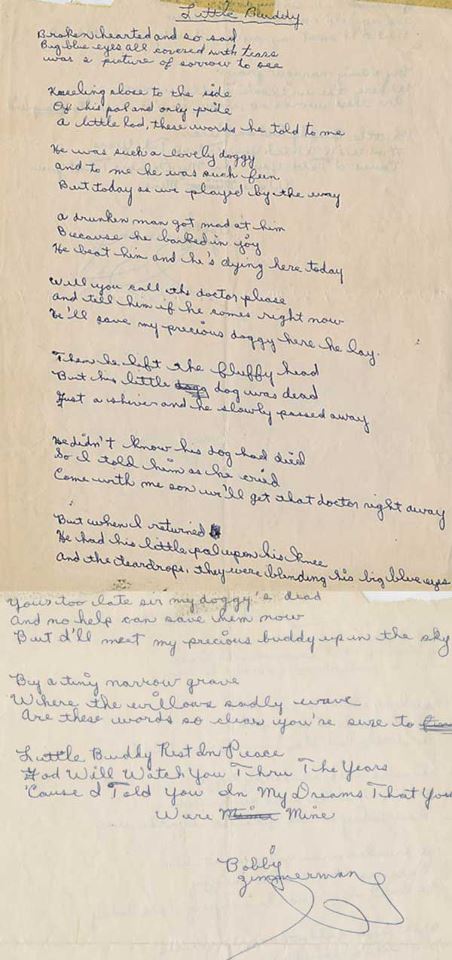

Little Buddy

A hand-written poem believed at the time to be by a teenaged Bob Dylan and signed Bobby Zimmerman is seen in this undated handout photo from Christie’s Auction House 19 May 2009.

It was at Herzl Camp when he ‘wrote’ a poem in 1957 and submitted it to The Herzl Herald, the camp paper. ‘Little Buddy’ turned out to be a Hank Snow song. Uh-oh! wink ifade simgesi

Hank Snow’s version of “Little Buddy”

Broken hearted and so sad, golden curls all wet with tears,

‘Twas a picture of sorrow to see.

Kneeling close to the side of his pal and only pride,

A little lad these words he told me.

And…

Bobby Zimmerman’s version of “Little Buddy”

Broken hearted and so sad

Big blue eyes all covered with tears

Was a picture of sorrow to see

Kneeling close to the side

Of his pal and only pride

A little lad, these words he told me

https://www.reuters.com/

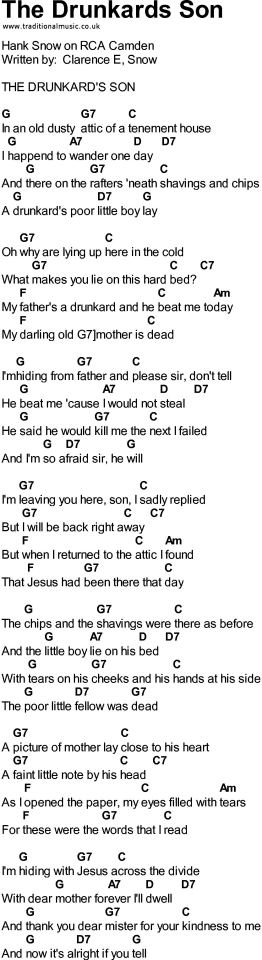

“Little Buddy” appears to be the second known transcription Bob made of a Hank Snow song as a young man. The first was “The Drunkard’s Son,” a lugubrious tune with a sentiment closer to Victorian times than 19 and 47, which is when Snow originally released it on the Bluebird label. “The Drunkard’s Son” was re-released in April 1950 on the RCA Victor label, and is very probably another 78 that Bobby Zimmerman owned.

“In the summer of 1957, I was a camp counselor at Herzl. On the first day, we welcomed the campers who arrived almost exclusively by bus or car. An unusual event was the arrival of several campers on two motorcycles from Hibbing, Minnesota. One of the motorcycle campers was Robert Zimmerman, guitar slung over his shoulder, and as I recollect, the other was Louis Kemp, who wrote a recent article in Moment about his celebrity Seder with Marlon Brando. Already known as a rebel, rumor had it that Robert Zimmerman had received his motorcycle as a parental gift for agreeing to attend Herzl camp!

Robert, joined occasionally by a few other campers, spent most of his time singing and playing his guitar and not participating in most organized camp activies. According to my recollection it was especially hard to get him to participate in athletics. Despite being a teenager and camp rebel, he was an intelligent and friendly kid who was well-liked by his fellow campers and counselors. He remained friendly with my brother David, who also attended camp that summer, and occasionally through the years, stopped in at his bookstore, The Hungry Mind, on Grand Avenue in St. Paul, Minnesota. My enduring memory of Bob Dylan from that summer is of a young man sitting on the roof of one of the cabins, strumming on a guitar and singing loudly with his characteristic high-pitched nasal twang.”

— Joel Unowsky, Gaithersburg

https://www.shmoozenet.com/

Apparently, Abe had a different impression of son Bob’s final camp year (1957) at Herzl. Abe told Robert Shelton: “When he was sixteen, he took over the camp. He was leader of the camp, the Rabbi told me.” Perhaps, the Rabbi was saying one thing, but Abe was hearing something entirely different.

In 1993 the Dylan fanzine Isis had published the text of a ‘poem’, written in Bob Zimmerman’s own hand, the original of which had been posted by an unnamed hand to the fanzine’s editor, Derek Barker.

This ‘poem’ was a mournful tale narrated as if by a scared boy in hiding to avoid being beaten by his drunkard father. Five issues later, reader John Roberts wrote in to say that he had found an album on the cheap RCA Camden label, dated 1962, titled The One and Only Hank Snow, and risked wasting his 75p on this unknown music because of its inclusion of a song, credited to Hank Snow’s original name, Clarence E. Snow, titled ‘The Drunkard’s Son’ and handily summarised in the sleeve notes as ‘the mournful tale of a scared boy in hiding to avoid being beaten by his drunkard father.’ Yes indeed.

As Roberts nicely observes, if the ‘Zimmerman Transcript’ is authentic, which now seems established, it is a ‘truly unique document—the first evidence we have of Bob’s plagiarism!’ Ironically, it’s an example of Snow’s plagiarism, too. Look back at the Jimmie Rodgers catalogue, and there, recorded in Atlanta in 1929, is Rodgers’ ‘A Drunkard’s Child’.

Perhaps it was still in Hank Snow’s repertoire when Dylan, in his youth, was in the audience for his show at the Veterans Memorial Building, Hibbing. Dylan mentions this in Chronicles Volume One—and a few pages later writes that before he encountered Woody Guthrie, when Hank Williams had been his ‘favorite songwriter’, Hank Snow had been ‘a close second’.

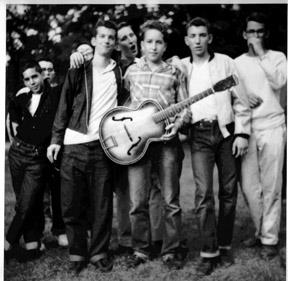

Bob Zimmerman, Camp Herzl, 1957.

?, Paul Black, Larry Kegan (dark jacket), Jerry Waldman (singing), Bob Zimmerman, Louie Kemp, David Unowsky.

Photograph courtesy of Leon (Aryeh) Spotts, a Herzl counselor, via Mark Alpert.

“It was the summer of 1957 and I don’t remember many details. Do I remember him sitting on a roof with his guitar? Yes. Am I sure it was the bet-hak? No. I remember that Bob didn’t join in much of the sports and arts and crafts. I think he was busy with girls. Did I think he was a future genius musician, poet, etc.? No. I do have a recollection of our cabin taking our turn at putting on a show in the Ulam. To say it was post-modern and non-linear would be a large understatement.” — David Unowsky, Bob Zimmerman’s cabin mate

A recording of Bob Zimmerman was made earlier than this in a custom recording facility in the Terlinde Music Shop in St. Paul, Minnesota, on Christmas Eve, 1956! He and two friends from summer camp, Larry Kegan and Howard Rutman, are all aged 15; Bob is on piano and shares vocals with the others as they race through incomplete versions of eight songs in little more than nine minutes.

The songs are: ‘Let the Good Times Roll’ (an R&B million-selling instant classic that year by Shirley & Lee: a record that’s been giving pleasure ever since), ‘Boppin’ the Blues’ (a small hit by Carl Perkins, also 1956), an unidentified song with almost no lyric beyond the phrase ‘Won’t you be my girl?’, ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ (Lloyd Price’s first record and first hit, and one of the earliest black R&B records to cross over into the white markets and so to help shape rock’n’roll), ‘Ready Teddy’ (a 1956 Little Richard hit), ‘Confidential’ (a hit by Sonny Knight—a song Dylan would revisit on the Basement Tapes in 1967, live in Helsinki on May 30, 1989 and in the first two of his unusual four-set gig at Toad’s Place, New Haven, CT, on January 12, 1990), ‘In the Still of the Night’ (an R&B ballad by the Five Satins, also a hit the first time around in 1956, and often named as one of the most beautiful such records ever made) and ‘Earth Angel’ (a 2- million-seller by the Penguins from 1954). Clearly, one of Bob’s main musical enthusiasms at the time was for doo-wop.

In June 1986, with Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers, the night after he’d played Minneapolis, he performed ‘Let the Good Times Roll’ in East Troy, Wisconsin, introducing it thus: ‘This is pretty old. I used to play this when I was twelve years old. And this is a song that got me booed off my first stages. It was a different band, but it sort of went the same way.’

“When Bob traveled down to St. Paul he stayed with the parents of his new friends. Howard Rutman’s family had a piano in their basement. “He would bang the shit out of the piano,” says Rutman. “He would get up there and dance on the damn thing…. Ah God, he just ruined it.” They went driving and parked in front of the house to talk late into the night, whiling away time until their favorite radio program, Lucretia the Werewolf, came on. “We were a real close-knit group,” says Rutman, who recalls discussing big subjects like war and man’s inhumanity to man. Still, Bob stayed very much to himself. “A great deal he kept to himself because he was a very, very inward type,” says Rutman. “He’s always been that way.” Music was Bob’s preferred form of expression. In everyday life he was a quiet kid. When he sang and played music he became somebody else altogether, a complete extrovert. He also lost himself in films.”

Sounes, Howard. Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan. New York: Grove Press, 2001, 0802116868, pages 46-47.

Howard Rutman’s father Harvey was first cousin to, and best friend of, the Joseph Rutman who eventually married Beatty Zimmerman, many many years after their first spouses had died. So Howard and Bob, decades down the road from their teenage comradeship, have ended up related by marriage.

“Louis Kemp [1941? – ] has been an almost life-long friend of Bob Dylan’s, since first meeting him at a Jewish co-educational summer camp, Camp Herzl, which they both attended annually in the mid-1950s.

Louis inherited the long-established family business of A. Kemp Fisheries Inc., based at 4832 West Superior Street, Duluth, which had been founded in 1930 by Aron and Abe Kemp, who started taking Lake Superior fish to the Chicago markets. It’s a company whose relationship with Swedish and Finnish fishermen goes back a long way. There’s a statue to the memory of these men on the shore at Green Point, just north of Thunder Bay, erected in 1990 on the 100th anniversary of their trading. ‘The Finns of Green Point would sell their fish to Kemp Fisheries located in Duluth,’ noted Mike Roinila in a 1997 article, ‘and over the years a trusting and lasting association was formed between the fishermen and the American seller. . . . [And] when an unexpected thaw one winter left the fishermen with no way to keep their harvest frozen, Kemp Fisheries rented out the Port Arthur arena to freeze the fish and preserve them for market.’

Today’s marine traffic is mostly boats used by the owners of the shoreline cottages—Green Point’s last commercial fisherman retired in 1990—but A. Kemp Fisheries survived. Louis Kemp took over in 1967, expanded into Alaska and re-named it Louis Kemp Fisheries in 1986, and has since seen it taken over and moved. It was taken over first by Tyson Seafood (1992) and then by Bumble Bee (1999). Bumble Bee is a subsidiary of International Home Foods, which was itself taken over in 2000 by ConAgra Foods, which moved production from Duluth to Motley, Minnesota. Its official address is now in Downer’s Grove, Illinois. They mostly turn North Pacific white fish pulp into imitation shellfish (surimi), and Louis Kemp has become a registered trade mark; you can buy Louis Kemp Crab Delights in Chunk Style, Flake Style, Leg Style or Easy Shreds; Lobster Delights Salad Style, and Scallop Delights Bay Style.

Kemp was among the entourage on Dylan and The Band’s 1974 ‘comeback’ tour, and with Barry Imhoff was tour manager on the Rolling Thunder Revues—on which, SAM SHEPARD noted, he showed ‘a remarkable gift for being able to speak words without moving his mouth,’ and also ‘managed to buy a 1934 Packard coupe´’. At The Band’s so-called ‘Farewell Concert’ dinner in San Francisco on November 25, 1976, Kemp Fisheries supplied the smoked salmon. It was even through his fisheries that he became a friend of Marlon Brando’s, and duly brought Brando and Dylan together for a very different kind of meal. As his own account of 2005 explains it:

‘I got to know Marlon about thirty years ago through a mutual friend. His son, Christian, came to work for me in fisheries I owned in Alaska and Minnesota. . . . One of my visits to Los Angeles coincided with Passover. I was not yet Orthodox and made plans to attend a seder at a local synagogue with my sister. Marlon called me that very day and invited me out to dinner. I graciously declined, explaining that it was Passover and I was going to a seder. Marlon became audibly excited over the phone and said, ‘‘Passover— I’ve always wanted to attend a seder. Can I come with?’’ He had made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. . . . A short time later, Marlon called me back and asked if he could bring a friend. I said, yes, by all means. . . . I called the shul again. They were a little less patient this time and begrudgingly told me that they could squeeze one more person in, but this was absolutely the last one as they were now officially sold out.

‘Still later that day, I received a phone call from a childhood friend of mine who had become a well-known singer/songwriter. . . . he asked if he and his wife could go along. The shul was unhappy . . . but somehow I softened the heart of the receptionist and she agreed to let my people go—to the seder.

‘I will never forget the sight of our table in the synagogue, Marlon Brando was to my left and David Kemper sitting next to him was his guest. This was during the height of Marlon’s involvement with Native American causes and he had brought with him noted Indian activist Dennis Banks of Wounded Knee fame. Banks was dressed in full Indian regalia: buckskin tassles on his clothes and long braids hanging down from a headband, which sported a feather. My childhood friend Bob Dylan sat to my right, joined by his wife, my sister Sharon, and other friends. . . . After about forty-five minutes, the rabbi figured out that ours was not your average seder table. ‘‘Mr. Brando, would you please do us the honor of reading the next passage from the hagaddah,’’ he said. Marlon said, ‘‘It would be my pleasure.’’ ‘He smiled broadly, stood up and delivered the passage from the hagaddah as if he were reading Shakespeare on Broadway. Mouths fell open and eyes focused on the speaker with an intensity any rabbi would covet. When he was done I think people actually paused, wondering if they should applaud.

̶

‘Somewhat later the rabbi approached another member of our table. ‘‘Mr. Dylan, would you do us the honor of singing us a song?’’ The rabbi pulled out an acoustic guitar. . . . Much to my surprise Bob said yes and performed an impromptu rendition of ‘‘Blowin’ in the Wind’’ to the stunned shul of about 300 seder guests. . . . Needless to say, everyone was both shocked and thrilled by this unusual Hollywood-style Passover miracle.’

But Louis Kemp seems always to have remained important at least in part because of his preshowbiz credentials with Dylan. ROBERT SHELTON reported that it was with Kemp, in September 1974, that Dylan ‘revisited Highway 61, touring the North Country . . . [and] showing his oldest children where he’d grown up’.”

Gray, Michael. The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. New York: Continuum, 2006, 0826469337, pages 375-376.

Bob Zimmerman 1957

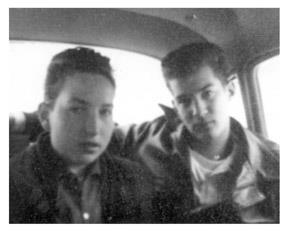

Larry Kegan on left, Bob Zimmerman on the right, Camp Herzl, 1957.

Bob Zimmerman, Larry Kegan, 1957.

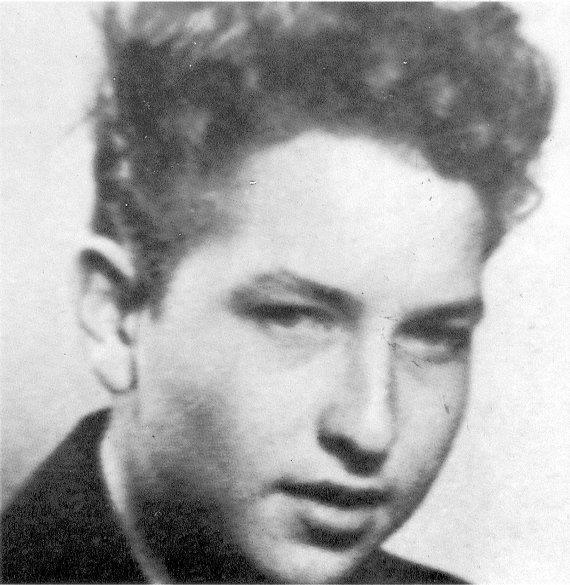

Bob Zimmerman 1957-58

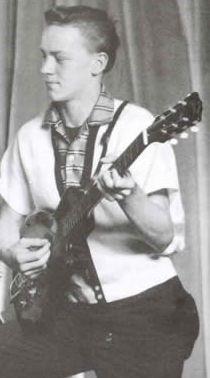

Hibbing High School, September 1958.

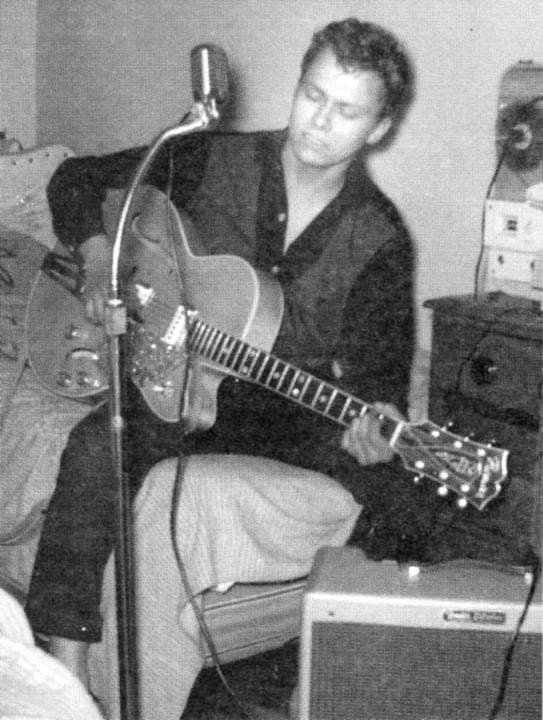

This photograph was taken by Bob’s mother, Beatty, in Hibbing, and dated September 1958, a 17-year-old Bob is shown with his second electric guitar. Most more youthful rock’n’roll moments seem to have him on piano.We can say for certain from the photograph that this electric instrument is not a Fender (it’s sometimes been said that he owned a Fender in Hibbing)—and we can say that it isn’t his first electric, a $39 turquoise Silvertone bought mail-order from Sears Roebuck, but must be his second, a new Supro Ozark (a guitar Jimi Hendrix also had as a lad), bought at Mr. Hautala’s store in Hibbing at a knock-down $60 because Bob and his friend John Bucklen each bought one at the same time: and September 1958 is too late for him to be just acquiring the Silvertone. This is the picture of a boy who’s proud of having upgraded. In Minneapolis, Bob swaps his electric for an acoustic. From there he emerges as an acoustic playing folkie, and remains so until July 1965.

Gray, Michael. The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. New York: Continuum, 2006, 0826469337, page 285.

“John Bucklen soon became the closest friend Bob had in Hibbing. He was six months younger than Bob, and a year below him in high school. His father, a disabled mine worker, was an accomplished musician who enjoyed a wide variety of music. His sister, Ruth, had a record player. The boys began to spend a lot of time at each other’s houses, although Bucklen got the impression Abe may not have approved of the friendship as he seemed to frown upon most of Bob’s friends.

“During jam sessions with Bucklen, Bob mixed up snatches of pop tunes with song ideas of his own. The first song Bob invented was about actress Brigitte Bardot. Bob played his parents’ white baby grand, and Bucklen accompanied him on guitar. Bucklen had a tape recorder and they recorded the sessions, interjecting juvenile humor and bits of hipster slang, as if making their own radio show. When they got tired of the game, they headed over to Crippa’s where they could listen to records in the sound booths. On visits to see his relatives in Duluth and the Twin Cities Bob was able to visit bigger stores that stocked the race records he liked.”

Sounes, Howard. Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan. New York: Grove Press, 2001, page 44f.

====================

John Bucklen tape (1958)

The Home of Bob Dylan

Hibbing, Minnesota

1958

1. Hey Little Richard

2. Buzz, Buzz, Buzz (Gray/Byrd)

3. Jenny, Jenny (Johnson/Penniman/Crewe)

4. Blue Moon (Lorenz Hart/Richard Rogers)

Zimmerman:

This is Little Richard…(fakes wild crowd noises into microphone) …Little Richard’s got a lot of expression.

Bucklen:

You think singing is just jumping around and screaming?

Zimmerman:

You gotta have some kind of expression.

Bucklen:

Johnny Cash has got expression.

Zimmerman:

There’s no expression. (sings in boring, slow and monotone voice): “I met her at a dance St. Paul Minnesota… I walk the line, because you’re mine, because you’re mine…”

Bucklen:

You’re doing it wrong, you’re just –

<end of broadcast tape segment>

Bucklen:

What’s the best kind of music?

Zimmerman:

Rhythm and Blues.

Bucklen:

State your reason in no less that twenty-five minutes.

Zimmerman:

Ah, Rhythm and Blues you see is something that you really can’t quite explain see. When you hear a song Rhythm and Blues – when you hear it’s a good Rhythm and Blues song, chills go up your spine…

Bucklen:

Whoa-o-o!

Zimmerman:

When you hear a song like that. But when you hear a song like Johnny Cash, whadaya wanna do? You wanna leave, you wanna, you – when you hear a song like some good Rhythm and Blues song you wanna cry when you hear one of those songs.

<end of broadcast tape segment>

after Jenny Take A Ride:

Bucklen:

Listen, man you gotta to do it a little bit faster than that. I mean I’m trying to cut a fast record here, that’s right …

Zimmerman:

I can’t help it.

Bucklen:

I know it ain’t slow but it’s not fast enough too.

Zimmerman:

Whadaya talking about, man, that’s plenty fast!

Bucklen:

No, it isn’t.

Zimmerman:

That’ll sell – that’ll sell (clicks fingers) just like that – ten million in a week! Weeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee

Bucklen:

What are you trying to do man, coming in with ‘weeelll’ like that? I mean ….

Zimmerman:

Well that’s for the new song and I’m starting another one.

<end of broadcast tape segment>

after Blue Moon:

Zimmerman:

Yeah, ah, Ricky Nelson. Now Ricky Nelson’s another one of these guys. See Ricky Nelson, Ricky Nelson –

Bucklen:

Ricky Nelson is out of the question.

Zimmerman:

Well he copies Elvis Presley! Yeaah, it’s perfectly…

Bucklen:

He can’t do like Elvis Presley.

Zimmerman:

Well he can’t sing at all, Ricky Nelson. So we may as well forget him. See I mean – I mean, ya know when you hear music like The Diamonds. For instance The Diamonds are really cool, they’re out on the street really popular, really record [?], you know. So they’re popular big stars but where, where do they get all the songs? You know they get all their songs, they get all their songs from little groups. They copy all the little groups. Same thing with Elvis Presley. Elvis Presley, who did he copy? He copied Clyde McPhatter, he copied Little Richard, …

Bucklen:

Wait a minute, wait a minute!

Zimmerman:

…he copied the Drifters

Bucklen:

Wait a minute, name, name, name four songs that Elvis Presley’s copied from those, from those little groups.

Zimmerman:

He copied all the Richard songs –

Bucklen:

Like what? –

Zimmerman:

“Rip It Up”, “Long Tall Sally”, “Ready Teddy”, err … what’s the other one…

Bucklen:

“Money Honey”?

Zimmerman:

No, “Money Honey” he copied from Clyde McPhatter. He copied “I Was The One ” – he copied that from the Coasters. He copied, ahhh, “I Got A Woman” from Ray Charles.

Bucklen:

Er, listen that song was written for him.

https://www.punkhart.com/

————————–

Jams/Rehearsals – mostly at the Zimmerman house (1957):

(1) With John Bucklen:

(a) Improvisations to Gene Vincent’s record:

At Crippa’s Howard Street music store, Bob grabs a Gene Vincent album. At Feldman’s clothing store, they buy blue caps with little visors, like Vincent’s boys wear in the movies. Back in Bob’s room, they spin the record while John pretends to bang a guitar and Bob takes the part of the rockabilly rebel: Be bop a lula she’s ma bay-ba…be bop a lula don’t mean may-ba.

(b) Recordings with piano backing:

With John’s Sears Silvertone tape recorder on Bob’s piano, they attempt songs; Bob pounds chords and John kind of tinkles along on the higher keys. They mimic Stan Freberg, a popular comic who has parodied Elvis, Belafonte and “Sh-Boom.” When they ad lib, the sessions can get raunchy.

You ain’t nothin’ but a horehound.

A couple of kids smoking, coughing, joking, laughing, screaming.

“The Diarrhea Blues.”

Bob’s and John’s voices are nearly indistinguishable.

Next, it’s John, singing Buddy Holly’s “Peggy Sue.”

Briefly, lyrics fall into place, backed by Bob’s four chord progression, now sounding vaguely like “Earth Angel” or something by the Turbins or Crests.

Bob’s voice is clear and almost sweet: I wanna rock-I wanna cry – I wanna rock-I wanna cry-

Bob narrates, like Gatemouth. Jive talk. Blues. Dig the rebop, daddy-O.

With Bucklen: Daddy Cool, Daddy Cool … cool Daddy … Daddy who? Daddy Cool!

(A few lines to Barbara Hewitt who’d dumped Bob before anything had gotten started): I got a girl, she lives on a hill, she’s my baby and I love her still. Barbara won’t you come back to me? I need your lovin’.

When he hammers into Little Richard, his voice becomes harsh and strained. Don’t I sound just like Jerry Lee Lewis?

(c) Recordings w/guitar backing:

In Bucklen’s bedroom, they record with acoustic guitar backing instead of piano.

Long Tall Sally. Tutti Frutti.

Jenny Jenny, Whooo. Jenny Jenny.

Bob sings about his friend, LeRoy Hoikkala: Lee Roy—LEE Roy

Engel, Dave. Dylan in Minnesota: Just Like Bob Zimmerman’s Blues. Rudolph, Wisconsin: River City Memoirs-Mesabi, 1997.page 153f

Hautala Music Store

2218 1st Avenue

Hibbing, Minnesota

Bob’s second electric guitar, a new Supro Ozark, bought at Mr. Hautala’s store in Hibbing at a knock-down $60 because Bob and his friend John Bucklen each bought one at the same time.

The store later became Bigelow Appraisals.

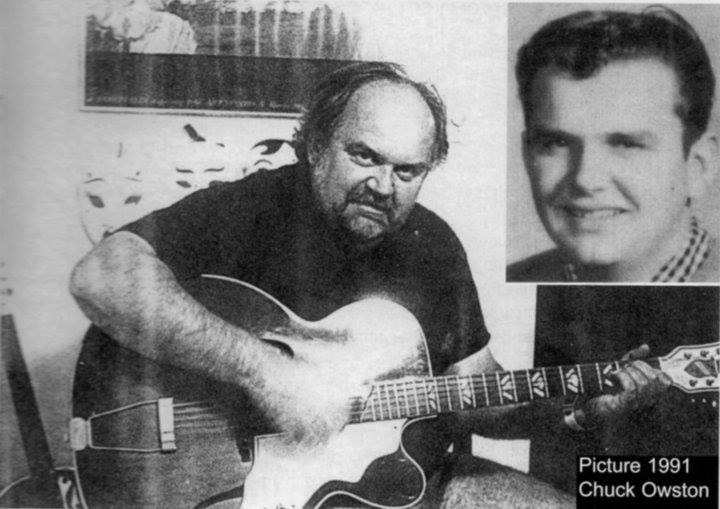

Dick Kangas in his bedroom “studio” also used by Bob Zimmerman

A party in Virginia, Minnesota.

Guitarists: John Bucklen, left; Dick Kangas, right.

Note John Bucklen’s black solid-body sunburst-fiinish Ozark Supro electric guitar. He and Bob Zimmerman each got one for $60.00 a piece, a discount as they bought two. — Virginia Minnesota‘da

The Pogues at Hibbing High School?

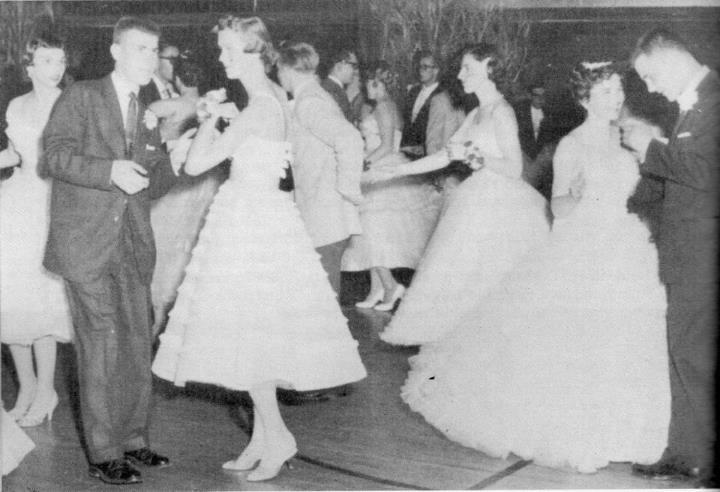

Junior Prom, 1958 (1959 Hematite photograph)

Held in the boys’ gymnasium, 2 May 1958, from 9-12 p.m., the Junior Prom features conventional dance music by George Pogue’s orchestra. The theme is “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered.”

Echo’s sister comes over from her house next door to take pictures of Echo in a pale-blue, floor-length gown, accented by a corsage from Bob.

Bewitched.

Before the Prom, Bob insists he and Echo drive thirty miles to Virginia to see Jim Dandy.

Bothered.

Still, when they arrive (a little late), there is possibility in the glittering three-dimensional stars beneath a ceiling of blue, silver, and gold streamers. Outlining the dance floor are white trees draped with pink angel hair and surrounded by silver stars.

Bewildered.

But who could feel more out of place among so much Hibbing High School pride? Bob is as poor a leader as she is a follower. He takes “little teeny steps” and keeps saying, “What’s the matter, can’t you dance?”

Can’t you dance?

Finally, he says, “Let’s get out of here.” A post-Prom supper dance is held at the Moose Lodge club rooms for the righteous; but Bob and Echo fall asleep in the car. Later, they find out the pictures her sister took do not turn out.

Echo Helstrom

” 20 below zero,

and running down the road in the rain

with yo´ ol´ man´s flashlight on my ass.

Now yo´ mother shines it in my face.

when we sat and talked in the L&B ´til two o´clock at night.

I was such a complete idiot, thinking back,

that the car was in the driveway all night.

Let me tell you that your beauty is second to none,

but I think I told you that before.

Well, Echo, I better make it.

Love to the most beautiful girl in school.

Bob”

Echo Hellstrom´s 1958 Hibbing High School Yearbook, Hematite

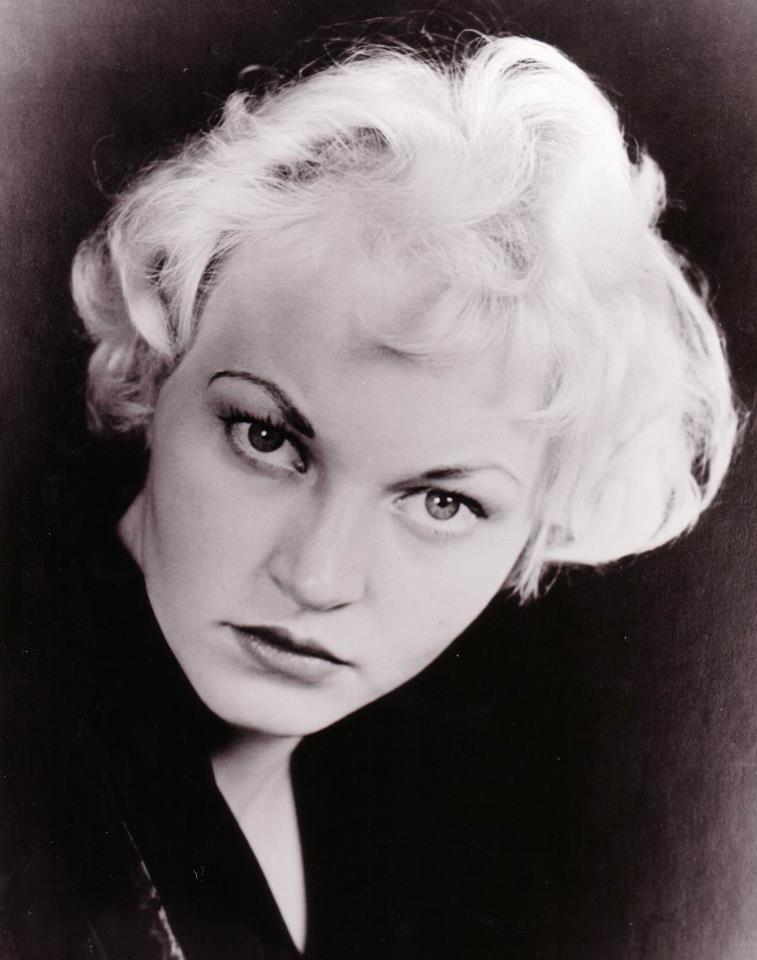

Echo Star Helstrom met Bob Zimmerman in the 11th grade.

She was free-spirited and blonde from a less-affluent section of town than the Zimmerman family and has been frequently cited as the inspiration for the classic folk ballad “Girl from the North Country”.

In his memoir Chronicles Volume One, Bob Dylan writes “Everyone said she looked like Brigitte Bardot, and she did.”, which raises interest because Dylan stated in a 1961 interview “I dedicated my first song to Brigitte Bardot.” And at one of his first public performances, in his high school auditorium, he sang a song beginning “I got a girl and her name is Echo…”

Also importantly, he recounts in Chronicles: “One of the reasons I’d go [to Helstrom’s house]… was that they had old Jimmie Rodgers records, old 78s in the house.” He readily absorbed musical influences and this record collection seems also to have played a part in Bob Dylan’s musical development.

“I once wrote a junior high school term paper on music like that. Colored jazz, with a big beat. They wouldn’t let me write on rock and roll. That wasn’t a fit subject, my music teacher said. Oh, Hibbing is SO hokey.”

“Bob was a lot luckier with his teachers. He had that nice Mrs. Peterson in music, for one thing, and that made all the difference in the world. The woman I had practically ruined my life. That whole eleventh grade when Bob and I went steady, he had the music teachers snowed. Nobody else could stand how he sung or what he played especially the electric stuff, but people like Mrs. Peterson and Bob’s English teacher, Mr. Rolfzen, they had a feeling. Bob would play for anybody, anytime, and I guess that enthusiasm made a difference, too. He was such a sweet convincer.”

“… ‘Robert, you have green teeth,’ my mother used to say, and she would tell him either to go brush his teeth and take a shower, or not come to the dinner table. My mother was the only person I ever knew who could make Bob mind. And the only one who could talk to him like that, and not make him mad. Bob was an extremely headstrong young man …”

Helstrom, Echo [1942 – ]

Marvel Echo Star Helstrom Shivers was born in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1942, by far the youngest child of mechanic, painter and welder Matt Helstrom and his wife Martha. Her brother (also named Matt) was 14 years older than her, and her sister (also named Martha) 15 years older. She was, as she said herself, ‘from the other side of the tracks’ from the middle-class Robert Zimmerman; and this was part of her fascination for him: ‘he was rich folk and we were poor folk,’ as she told Robert Shelton. There was another difference too: ‘he was Jewish and we were German, Swedish, Russian, and Irish, all mixed together.’ In fact, Echo’s mother was born in Ohio and her father in Minnesota, but all four of her grandparents were from Finland.

In the 2005 film No Direction Home Dylan says that before Echo there had been another girl, with, for him, an equally resonant name, ‘Gloria Story’; but until he volunteered it, no such name had ever been mentioned in his biography, whereas Echo has long and famously been his ‘Girl of the North Country’. It’s sometimes been guessed— in the dark, either way—that Bonnie Beecher, aka Jahanara Romney, was the ‘real’ girl whose hair ‘rolled and flowed all down her breast’, but Echo has the better claim: she’s the one from Hibbing rather than Minneapolis, and she came first. She had taken accordion lessons, played the harmonium the Helstroms had at home and sang in the school choir. Like Dylan, though, she was into rock’n’roll and like him listened to R&B on the late-night radio station that beamed all the way up from Shreveport, Louisiana. They ‘went steady’ in 1957–58, when they were 16. In the 1958 High School Yearbook Bob wrote against Echo’s name: ‘Let me tell you that your beauty is second to none. Love to the most beautiful girl in school.’ On May 2, 1958, they went to the Junior Prom together, in the school’s Boys Gymnasium, and both danced badly.

The Helstrom household was a wooden shack three miles southwest of Hibbing on Highway 73, to which Bob would often hitchhike out after school. Matt Helstrom didn’t approve of his daughter’s young man any more than the Zimmermans approved of Echo, but when he wasn’t around, Bob would play Mr. Helstrom’s three guitars, or listen to his Jimmie Rodgers records, and sing her songs out on their porch. In Chronicles, Dylan describes Echo’s father as ‘The kind of guy that’s always thinking that somebody’s out to take advantage of him’, whereas her mother ‘was the kindest woman—Mother Earth.’ Martha Helstrom (a name Shelton never gives, always calling her, irritatingly, ‘Mrs. Helstrom’) liked Bob, looked on the relationship with equanimity, and felt that Bob ‘seemed much more humble than his family. Both Echo and Bob seemed so sorry for the working people.’ Bob’s brother, David Zimmerman, told Shelton: ‘Bobby always went with the daughters of miners, farmers, and workers. He just found them a lot more interesting.’

In 1968, working as a film-company secretary in Minneapolis to support a child from a failed marriage (cold rain can give you the Shivers), Echo looked back to the events that must have seemed light years ago. Without trying to claim more than her due in Dylan’s story, she told Shelton that they had both felt outsiders together, both misfits in conventional, old-fashioned, narrow-minded Hibbing. ‘We weren’t like the other people at school in any way. I just couldn’t stand being like the other girls. I had to be different.’ Bob was going to be a pop star and Echo was going to be a movie star. Mrs. Helstrom remembered a time when they were going to get married and have a child. ‘They planned to call their child Bob, whether it was a boy or a girl. You know how teenagers are.’

They were drifting apart by mid-1958, with Bob making it ever clearer that he was going with other girls, and they broke up in early summer. She saw him around, but after he left for New York the next time she saw him was at the Hibbing High School Class of ’59 tenth reunion in 1969. Bob and Sara Dylan turned up unexpectedly, and so did Echo. They spoke briefly; Echo was among the old friends who asked for, and received, an autograph. He signed it before he recognised her, then said ‘Hey! It’s you!’ and said to his wife, ‘This is Echo!’, and signed her programme ‘To Echo, Yours Truly, Bob Dylan’. That same year saw the release, on Nashville Skyline, of the rerecorded ‘Girl of the North Country’.

They must either have met up or spoken on the phone again, after almost another decade’s gap, some time in the late 1970s: Echo told biographer Howard Sounes that it was 20 years after their schooldays relationship that Bob confessed to her new intimate detail about it.

Soon after talking to Shelton in 1968 (for a book that didn’t emerge till 1986) and more than 30 years before talking to Sounes, she had also talked— some might feel excessively—to Toby Thompson, the gawky young author of the first book to explore the subject of Hibbing in relation to Bob Dylan, Positively Main Street: An Unorthodox View of Bob Dylan, published in 1971. He had reached Echo first in October 1968, very soon after Shelton; she was still in her basement apartment in Minneapolis, and gave him the new information that once, when she’d been listening to one of Bob’s Hibbing bands practising, when she’d deciphered his voice from within the over-amplified whole, he ‘was howling over and over again, ‘‘I gotta girl and her name is Echo!’’ making up verses as he went along. I guess that was the first song I’d ever heard him sing that wasn’t written by somebody else. And it was about me!’

It’s always seemed likely that a song from aeons later, ‘Hazel’ on Planet Waves, was also, on one level, about Echo. The album is full of warm memorialising about the Minnesota years—‘the phantoms of my youth’, ‘twilight on the frozen lake’— and to hear ‘Hazel’—‘dirty blonde hair / I wouldn’t be ashamed to be seen with you anywhere’—is to feel a hunch that the song’s tender tale recollects fragments of feeling from the days when Echo and Bob were riding around, coming together from different sides of the tracks, united in wanting to get out of Hibbing—‘you’re going somewhere / And so am I’.

Gray, Michael. The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. New York: Continuum, 2006, 0826469337, page 305f

“Hohner Echo Harmonica, circa 1959. Very Good condition. In a custom clamshell case. A harmonica that was owned jointly by Bob Zimmerman and his friend Dale Boutang, played by both during their high school days in Hibbing, Minnesota. Manufactured by M. Hohner, this particular harmonica was chosen because the name of the model was the same as one of Bob’s girlfriends in high school, Echo Helstrom. The harmonica has been in the possession of Dale Boutang since their school days together, and Boutang has written a letter attesting to the provenance. “I was a classmate and close, personal friend of Bob Zimmerman, who later changed his name to Bob Dylan. Bob and I shared many of our harmonicas and guitars. This one such harmonica, which I ended up keeping from our high school days. I have had [it] in my possession ever since.” Perhaps the greatest testament to ownership of this item is Dale Boutang’s crudely scrawled name, along the black edge of the harmonica, between the metal plates.”

It sold for $6,380.00 (£3,190.00), twice the highest estimate, in 2006. It was later up for sale for $8,500.00 (5,425.00) from Royal Books, Inc., 32 West 25th Street, Baltimore, MD 21218.

Dale Boutang was also responsible for selling Bob”s 22-page handwritten high school paper on The Grapes of Wrath that Robert Edward Auctions sold in 2004 (which Bob gave to Dale to help him with his paper).

Dale Boutang has had remarkable luck finding things for auction. Do you believe Bob would have owned a harmonica jointly with another boy’s name on it? When Dale auctioned his 1959 yearbook with many signatures in it, he did not have anything there from his “close, personal friend” Bob.

Both rode motorcycles, so we should see motorcycle parts at auction soon. wink ifade simgesi Dale a Harley 74, Bob a Harley 45. He moved to Fairbanks Alaska and was an Alaska State trooper, then an investigator for the Federal Government.

Time Goes By

Swing Dad Swing

Zimmerman house, 2425 7th Avenue East, Hibbing, MN 55746, corner of 7th Ave East and 25th Street.

Zimmerman house

A two story, wood framed, flat roofed, stucco house and an example of the Mediterranean Modern style that could be found all over Hibbing in 1947. On the ground floor there was the kitchen, bathroom, dining and living room with a fireplace. Upstairs, a hallway connected three bedrooms. Bob Zimmerman lived in the house from 1948-1959.

“In 1948 Abe moved his family to 2425 7th Avenue, Bob’s primary childhood home. This was a two-story detached house two blocks from Hibbing High, where Bob and David enrolled, and a ten-minute walk from downtown where Abe worked.”

Sounes, Howard. Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan. New York: Grove Press, 2001, page 37.

Fireplace

While riding on a train goin’ west

I fell asleep for to take my rest

I dreamed a dream that made me sad

Concerning myself and the first few friends I had

With half-damp eyes I stared to the room

Where my friends and I spent many an afternoon

Where we together weathered many a storm

Laughin’ and singin’ till the early hours of the morn

By the old wooden stove where our hats was hung

Our words were told, our songs were sung

Where we longed for nothin’ and were quite satisfied

Talkin’ and a-jokin’ about the world outside

With haunted hearts through the heat and cold

We never thought we could ever get old

We thought we could sit forever in fun

But our chances really was a million to one

As easy it was to tell black from white

It was all that easy to tell wrong from right

And our choices were few and the thought never hit

That the one road we traveled would ever shatter and split

How many a year has passed and gone

And many a gamble has been lost and won

And many a road taken by many a friend

And each one I’ve never seen again

I wish, I wish, I wish in vain

That we could sit simply in that room again

Ten thousand dollars at the drop of a hat

I’d give it all gladly if our lives could be like that

Zimmerman house

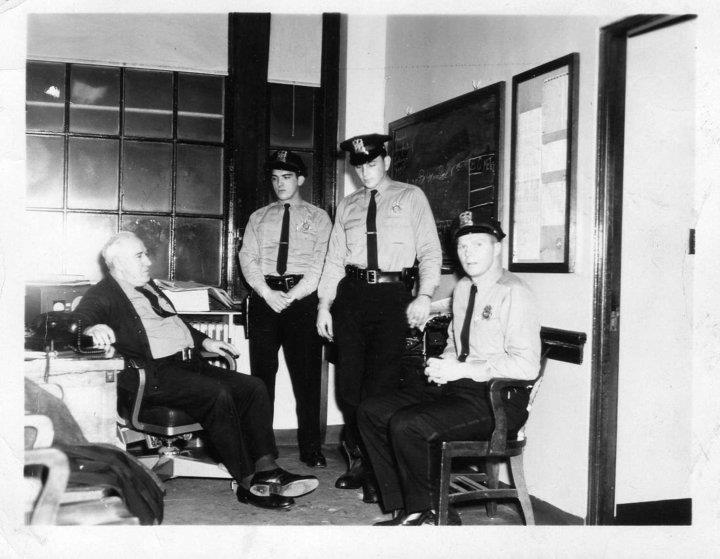

Police dealing with teen crime in Hibbing in 1958: Ed (Edward) Brigom, Dickie (Richard) Frider, Denny (Dennis) Romano, Archie (Archibald) Passeri.

The names are taken from what is written on the back of the photograph which belongs to Patrick Romano. Some insist it is Tom (Thomas) Motherway on the far right, and is too young to be Archie Passeri?

Oh, the age of the inmates

I remember quite freely,

No younger than twelve,

No older than seventeen.

Thrown in like bandits

And cast off like criminals,

Inside the walls,

The walls of Red Wing.

From the dirty old mess hall

You march to the brick wall,

Too weary to talk

And too tired to sing.

Oh, it’s all afternoon

You remember your hometown,

Inside the walls,

The walls of Red Wing….

It’s many a guard

That stands around smilin’,

Holdin’ his club

Like he was a king.

Hopin’ to get you

Behind a wood pilin’,

Inside the walls,

The walls of Red Wing

L & B Café, 417 East Howard Street, Hibbing, MN 55746. Bob and Echo would spend time at the L&B after school. They smoked cigarettes and played the juke box. Bob’s favorite order was cherry pie à la mode.

Braman’s Music, 208 East Howard Street, later Walkens Jewelry.

Here Bob Dylan learned to play the guitar in the 1950’s, taught by Raymond Blake. Kaye Krtinich worked part time at Braman’s while attending school and recalls Bob coming in for his lessons. She did not have much contact with him but remembers him being a quiet kid who paid her for the lessons.

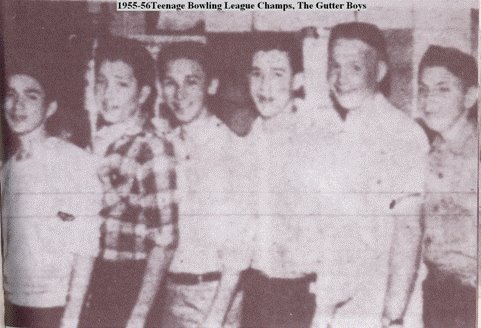

1955-1956 Teenage Bowling League Champs, The Gutter Boys, with Bob in the distinctive check shirt.

Hibbing Bowling Center, 1929 5th Avenue East, Hibbing MN 55746. The two upper stories of the building are gone.

— photograph courtesy of Jackie Chambers Rudnick 20120524

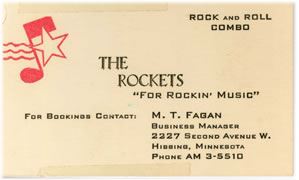

Common practice for local promotion and raising awareness. The Rockets join a Howard Street parade to promote an appearance. The same technique of mobilized public performance for self-advertisement had previously been employed by The Golden Chords.

— Photograph courtesy of LeRoy Hoikkala.

LeRoy Hoikkala in interview in On The Tracks #18:

“The convertibles…Bob had a ’54 Ford convertible, I had one also. They were used, but nice little cars. They were not expensive cars. We didn’t have new cars. We used (our cars) to promote our dances or rock concerts. We would get these big speakers, horns and two big amplifiers on top of my convertible and we would sit there playing, to advertise our dances. You don’t see that anymore!”

Crippa Music, 313 East Howard Street, Hibbing, MN 55746, opened in 1949 and sold sheet music and vinyl records. During the noon hour and after school Bob was known to stop by Chet Crippa’s and charge sheet music and records to his father Abe’s account.

“Gripped with a passion for music—particularly the blues—Bob wrote off for records he heard advertised on the radio. “Brother Gatemouth” Page sold records for Stan’s Rockin’ Record Shop in Shreveport, huckstering special $3.49 deals for six recordings. There was no way to buy this so-called race music in Hibbing as the assistant in Crippa’s music store downtown had never heard of the artists Bob liked.”

“The saleslady at Crippa’s explains that Bob doesn’t sell well in Hibbing. People don’t like his voice. Some of the other groups that do his songs — the Byrds, Peter, Paul and Mary, Joan Baez — they sell a whole lot better. But Saleslady likes Bob. She sold him his first harmonica. And harmonica rack. Had to order that special. Bob was in Crippa’s a lot. From the time he was just a little boy. Always fascinated by music. Would spend hours in the store listening to records. All kinds. Liked classical music at first. But, sometime during his junior high school years, he got interested in popular music. Blues, country, rock and roll, everything. Chet Crippa remembers ordering all of Hank Williams’ records for Bob, at one fell swoop. Chet outfitted Bob’s rock band too. With amplifiers, mikes, guitars, right down to picks and guitar strings. Chet remembers that in those days Bob carried his guitar with him wherever he went. An old beat-up Sears and Roebuck job, with a leather strap. Slung it over his shoulder and down his back, through snowstorms and everything.”

“Bob in those tight jeans he wore, with his hands squeezed into the pockets as far as he could get them, and he’d drag me into Crippa’s or one of the other stores that sold records. He’d walk up to the clerk like that in those jeans and with that kooky little grin, and ask for some records he KNEW they wouldn’t have. The clerk would say, ‘Little Who?’ or ‘Fats What?’ and Bob would say, ‘Well, how about such and such; or so and so’s new one?’ He’d keep that up until the clerk was just about furious, and then he’d put on his hurt look and we’d leave, ready to burst from not laughing.” — Echo Helstrom

The other source for the music was the far more powerful, big-time radio stations you could pick up even in the North Country. Dylan’s early girlfriend Echo Helstrom remembers listening to DJ Gatemouth Page, beamed up from Shreveport, Louisiana, in 1957, and Dylan was buying blues and post-war R&B records he’d heard on the radio from the age of 13, according to Stan Lewis, the legendary Shreveport record-store owner, plugger and radio-show packager, recollecting this in 1996:

‘DJs like Wolfman Jack . . . had shows on other independent stations willing to work R&B into their formats. One of those clear-channel stations had a 250,000-watt transmitter in Mexico. On certain nights its signal could be heard all over the country, even in Europe and South America. I couldn’t believe some of the places I started getting orders from.’ One place was Hibbing, Minnesota. ‘He used to call me at night, to order the records he’d just heard on the air. I thought to myself, Who is this rich kid, calling long-distance from the Midwest to order records? We’d chat and talk about the blues . . .’

Fifteen miles from Hibbing, in the small town of Virginia, MN, there was a DJ on station WHLB called Jim Dandy (real name James Reese), and in the summer of 1957 Dylan and his friend John Bucklen went over to find ‘the man behind the voice’, as Robert Shelton puts it. Bucklen told Shelton that after they found him, they visited him often. ‘He was a Negro, involved with the blues. He had a lot of records we like.’ Dandy’s was the only black family in town, and on radio he used a ‘white’ voice, which he dropped when he saw that Dylan and Bucklen were keen on black music. They spent many visits listening to R&B and blues records. As Shelton comments: ‘Through Jim Dandy, Bob discovered a new Iron Range that his family scarcely knew. That is why Dylan could say: ‘‘Where I lived . . . there’s no poor section and there’s no rich section. . . . There’s no wrong side of the tracks . . .’’’

Yet his first album, last year, made no particular impact on the people who knew Dylan as Bobby Zimmerman. One local record dealer lamented: “I ordered a dozen albums but even his relatives won’t buy them.”

Chet Crippa entertaining, 1950

Crippa Music, 313 East Howard Street, Hibbing, MN 55746, became Jerry Erickson’s Erickson’s Music which then became Chuck Rupar’s Rupar Music, which closed on 1 June 2012.

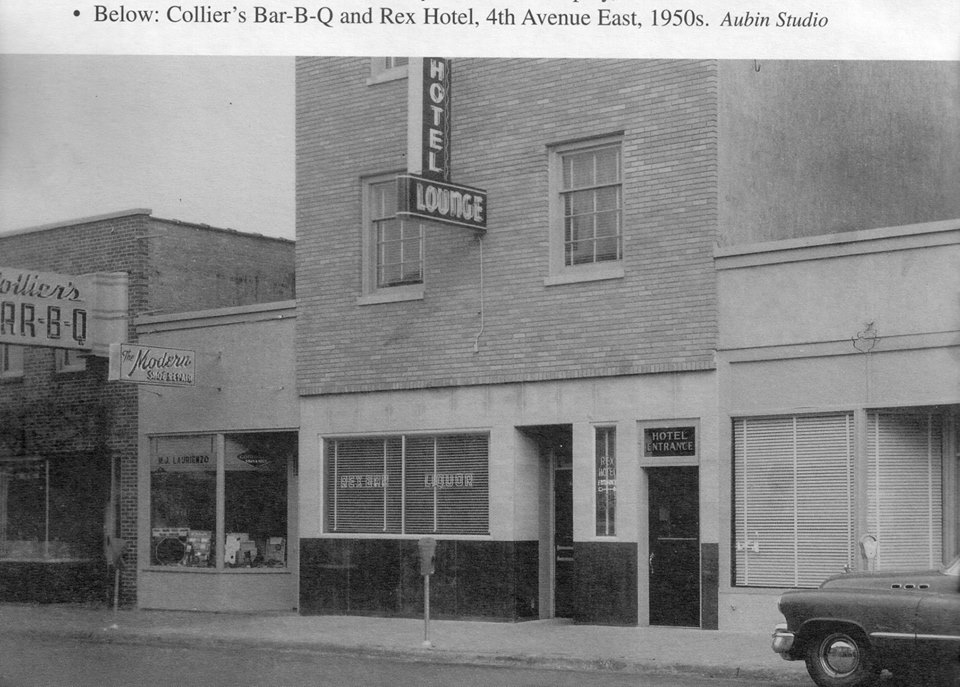

Collier’s Barbeque and Bar, 1928 4th Avenue East, Hibbing, MN 55746

Owned by John Von Feldt.

Collier’s Barbeque and Bar, 1928 4th Avenue East, Hibbing, MN 55746 became the Sugo Italian Restaurant. (Sugo means Tomato Sauce.)

— photograph courtesy of Jackie Chambers Rudnick 20120524

Collier’s Barbeque and Bar, 1928 4th Avenue East, Hibbing, MN 55746. Later it was the Open Range, it became the Chinese Dragon in the 1970s, then it became another Chinese restaurant, the Hong Kong Kitchen (also called the Hong Kong Restaurant) in 1981. (The Hong Kong Kitchen was still getting excellent reviews in 2009. The Hong Kong Super Buffet, 416 East Howard Street, which closed in 2011, is a totally different restaurant and a totally different building.) Later Collier’s became the Sugo Italian Restaurant. In 2015 Sugo closed.

The building was built in 1940.

The Golden Chords jammed at Collier’s on Sundays in late 1957 and early 1958. Bob’s final Hibbing band, Elston Gunn and the Rock Boppers, performed here during the summer of 1958. Collier’s Barbeque was a popular eatery and teen hangout. “Rose Von Feldt and her supportive family owned and ran Collier’s Bar-B-Q for many years. This restaurant was the forerunner to the coffee houses of the folk music era, as Robert Zimmerman, Jerry Von Feldt and assorted musicians gathered at Collier’s on Sundays to jam and play music for their friends, fellow students, etc. The door was always open…

“A second high school yearbook bearing Bob Dylan’s signature has been added to the exhibit at Ironworld in Chisholm called ‘Tangled Up In Ore: Bob Dylan and the Iron Range.’ The 1958 Hibbing High School yearbook is on loan from Jerry Von Feldt, a former classmate of Zimmerman’s …

In his message to Von Feldt, Zimmerman wrote, ‘Dear Jer, Well, the year’s almost over now, huh? Remember the ‘sessions’ down at Collier’s? Keep practicing the guitar and maybe someday you’ll be great.’ The message is signed, ‘A Friend, Bob Zimmerman.'”

— Chisholm, Minnesota, Monday 23 June 2008

Hibbing Lodge No 1510 Loyal Order Of Moose, 421 1/2 East Howard Street, Hibbing, MN 55746.

(Often mistaken in print as 1510 East Howard Street.)

The Moose Lodge had a piano and Bob Zimmerman made use of it.

Photograph courtesy of Toby Thompson. Echo’s hands on the pawking meter.

Moose Lodge

“See that lampost? Right in front of the Moose Lodge? That’s where I first met Bob. Well, it was in the L& B afterwards really, but there on that corner was where I first noticed him. How could I help it! He was standing in the middle of the sidewalk, playing the guitar and singing, and it must have been ten o’clock at night. He and the band had been rehearsing upstairs in the Moose Lodge, and they were all going into the L&B. ” — Echo Helstrom

Close up detail of sign:

P.A.P. Loyal Order of Moose Moose 1510.

Purity Aid & Progress.

Until May 1973 Moose Lodge membership had a racial requirement, it was open only to “male persons of the Caucasian or White race, who are of good moral character, physically and mentally normal, who shall profess a belief in a Supreme Being.” (Moose Lodge No. 107 v. Irvis, 407 U.S. 163 (1972)) The Court found that the Moose Lodge was “a private social club in a private building” and thus not subject to the Equal Protection Clause.

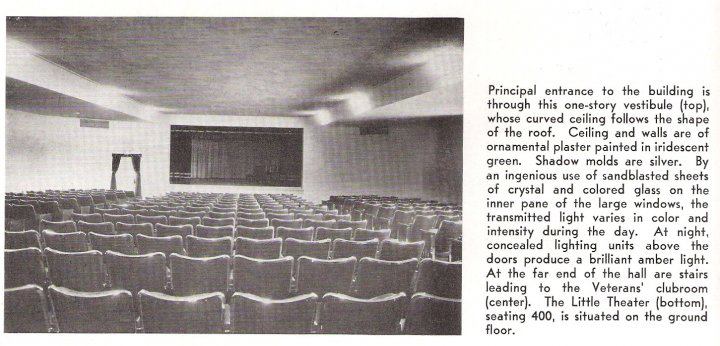

Hibbing Memorial Building

400 East 23rd Street, Hibbing, MN 55746

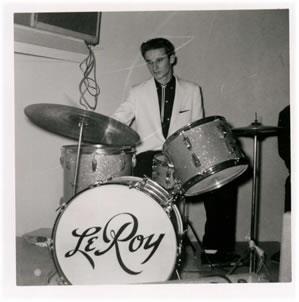

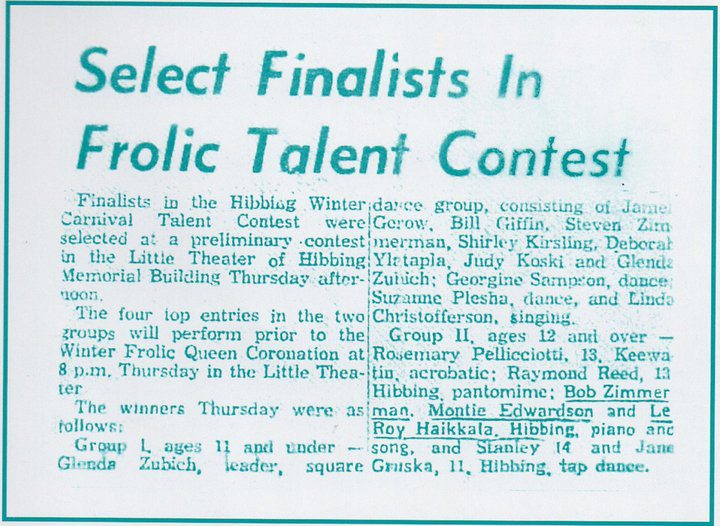

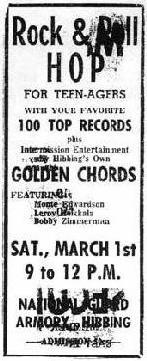

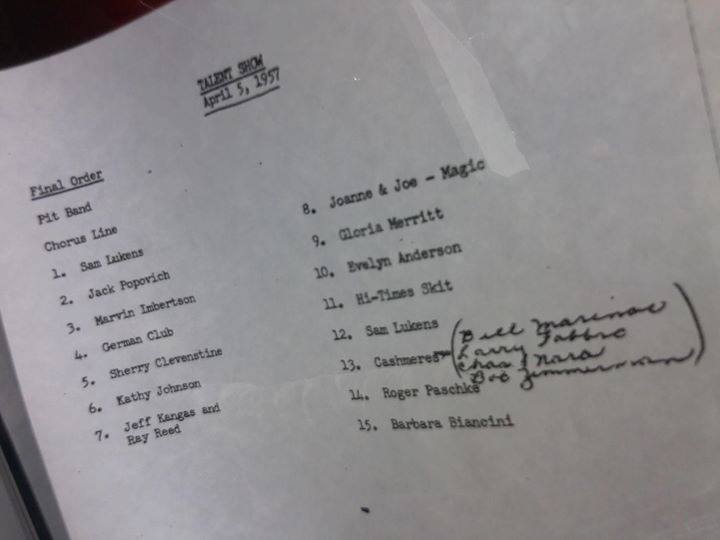

The Golden Chords — Bob Zimmerman, Monte Edwardson and Leroy Hoikkala — played a talent contest at the Memorial Building 400 East 23rd Street on Saturday March 1, 1958.

The piano and song group became Group II finalists in the afternoon preliminary round of the Hibbing Chamber of Commerce “Carnival Talent Contest”, part of the 1958 Winter Frolic festivities. The evening competition didn’t look too fierce, and Bob tells LeRoy, “We’re gonna take ’em.” Amidst shouts of “this is way too loud,” and “hold ‘er down,” the band plays on obliviously during the finals. High schoolers in the audience thought the band had won, but judges give way to older more conventional thinking. A13-yr old pantominist is declared the winner. An ecstatic Bob declares, “Hey, we really reached ’em. We knocked ’em dead.”

““Bob was a little detached [after the contest] saying, ‘We should have won, you know?’ Because, in fact the audience was with us, but they gave it to someone else.” — LeRoy Hoikkala

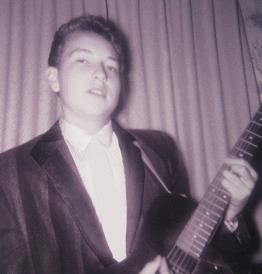

The Golden Chords, Little Theatre, Memorial Building, February 1958.

Bob Zimmerman, with Monte Edwardson and LeRoy Hoikkala.

“Bob had complete arrangements worked out in his head and he used us so that he could hear them come alive”

LeRoy: “He would write a song right at the piano. Just chord it, and improvise on it. I remember that he sang one about a train in R&B style”

During the Golden Chords days Bob, LeRoy and Monte worked out a song “Big Black Train”, the only Zimmerman-penned rock song known to exist.

Monte Edwardson: “He wrote a thing called “Big Black Train”, that we used to do. At the time I couldn’t believe one of us could just write a song.

Big Black Train

Well big black train, coming down the line

Well big black train, coming down the line

Well you got my woman, you bring her back to me

Well that cute little chick, is the girl that I want to see

Well I’ve been waiting for a long, long time

Well I’ve been waiting for a long, long time

Well I’ve been looking for my baby

Searchin’ down the line

Well here comes the train, yeah it’s coming down the line

Well here comes the train, yeah it’s coming down the line

Well you see my baby is finally coming home

LeRoy Hoikkala: ”He changed a lot of songs. He listened to a song and he changed them. He didn’t like the way they read. Just like a lot of the songs he recorded. I use to say that he wasn’t copying someone, but he took the basic song and if he didn’t like the lyrics he just changed it to what he wanted.”

John Bucklen: “It was difficult to tell which songs he wrote and which he didn’t write, because sometimes I’d discover that he said he wrote a song and he didn’t and other times I thought he did not write the song and he did. So, it was … pretty similar to the music we were interested in at the time.”

LeRoy: “He was improvising quite a bit. He would copy a lot of songs. He’d hear a song and make up his own version of it. He did a lot of copying but he also did a lot of writing of his own. He would just kind of sit down and make up a song and play it a couple of times and then forget it. I don’t know if he ever put any of them down on paper.”

“Big Black Train” was later, in fall of 1958, to be recorded by The Rockets at the Kay Banks studio in Minneapolis, for the Aladdin Record label, but never released. The Rockets was then Monte Edwardson, LeRoy Hoikkala, Jim Propotnick and Ron Taddei.

“..and we finished it on the way to the recording studio”. A handful of acetates exists. “ … used the others to get played on the radio.”

Bob 1965: “I never sang what I wrote until I got to be about eighteen or nineteen. I wrote songs when I was younger, fifteen, but they were songs. I wrote those. I never sang anything which I wanted to write. Y’understand? The songs I wrote at that age were just four chords rhythm and blues songs. Based on things that the Diamonds would sing, or the Crewcuts, or groups like that, the uh, the, you know,’In the still of the night’ kinda songs, you know.

LeRoy Hoikkala (Thin Man)

“I knew Bob pretty much from school and everything. Growing up you see each other. It is a small town. You know, everybody knows everybody in town. How we got to meet as far as playing in a band was Monte Edwardson–who is a guitar player; who is very good; he still plays today; he is a natural guitar player–we worked downtown, Monte and myself. Right across the street [from school], we met each other and we walked to a little job, an after-school job. And Bob was just there one day. Monte and I had been messing around with playing drums and guitar; just jamming a little bit. I had taken lessons for quite a few years. So, Bob just happened to say, “Hey, you guys going downtown?”

We actually walked from school to downtown, so we told him that we were playing, you know, just getting together and jamming around and playing. So, he said: “Hey, I’m playing piano, mouth-organ, harmonica and guitar. Maybe we could get together and kind of play a little bit.”

We said, “Yes, sure.”

So we started playing in Bob’s garage that was attached to his house, that little garage. We jammed in there for quite a bit, and we got a couple of jobs. The first time he ever got paid to do anything was with our band the Golden Chords.

Sometimes we’d go into the house to play, because he had a piano in the house.

It was just the three of us at that time. Me, Monte Edwardson and Bob. I played drums.

We played at the National Guard Armory, a pretty big building. We hired the police department, because you had to have the police, we hired people to collect tickets, we sold tickets, made tickets. We hired someone to clean the place up and everything, and we made money. It was kind of fun. It was one of those things where you put a lot of money out and do something; try to fix a Saturday night rock opera or “jam,” and a lot of kids came. That was probably the first time Bob ever was paid to do anything musically.

It was a dance. There was a wide-open area, no chairs, nothing, big stage, that’s all.

It was a onetime show, that particular one. That was kind of how we got together and started playing.

Then we played that talent show, you know, where we actually won but lost, because the kids went crazy [but the judges] gave it to someone else that tap danced. Bob was a little detached on that one saying, “We should have won, you know?” Because, in fact the audience was with us, but they gave it to someone else. We came in second. (He laughs.)

That was the three of us as the Golden Chords. The reason we called it the Golden Chords was because Bob was really…he could really chord with the piano and the guitar, really chord beautifully. He was really a natural at chording. And my drums were gold, sparkling gold. So, we said Golden…Chords, that´s how we got the name.

Ah, we played some of the Little Richard tunes, [like] “Jenny, Jenny.” Some of the southern type music, the blues songs…a lot of Little Richard. Bob loved Little Richard, so we did a lot of Little Richard stuff.

It was kind of new for the kids around here. We used to sit together with a reel to reel tape recorder at night and tape the AM-stations that came in really good at night. We taped it so we could listen to the new songs that didn’t come along here. Hibbing was kind of a backward-area. The last to get in.

So we listened to the songs from the AM radio, taped them and then Bob would play them, because that was more the type of songs that he liked; the bluesy songs. We listened to Shreveport, there were a bunch of DJs down there that we listened to.