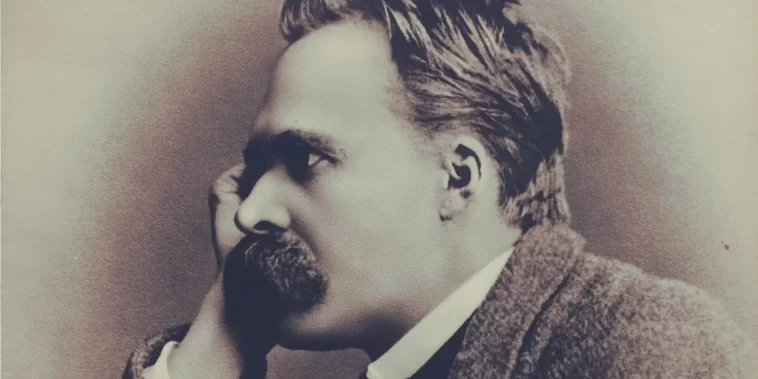

Understanding Nietzsche Through Schopenhauer and the Upanishads

To truly grasp Friedrich Nietzsche, one must first understand Arthur Schopenhauer; to understand Schopenhauer, one must turn to the Upanishads, the sacred texts of Hindu philosophy.

Western philosophy is often imagined as a self-contained story: beginning in the marble columns of Athens, developing through the salons of Paris, and shaping thought in the lecture halls of Berlin. On the surface, this narrative appears seamless and coherent, but a deeper look reveals hidden fissures. Beneath the familiar figures of Aristotle, Descartes, and other canonical thinkers, subtle Eastern threads—echoes from the misty peaks of the Himalayas and chants along the banks of the Ganges—flow quietly through the veins of Western metaphysics.

Within Europe’s self-conceived intellectual sovereignty, these unnoticed Eastern threads operate continuously. Schopenhauer transported these threads into Western thought, and Nietzsche wove them into a radical philosophical tapestry, one that affirms life in all its contradictions.

Schopenhauer and the Eastern Influence

Arthur Schopenhauer is known as the 19th-century pessimist metaphysician. He was among the first Western thinkers to seriously engage with Hindu and Buddhist philosophies, particularly the Upanishads.

The Upanishads present concepts that profoundly shaped Schopenhauer’s thought:

- Brahman, the ultimate reality beyond appearances

- Maya, the illusory nature of the observable world

- Samsara, the endless cycle of existence

Schopenhauer interprets the world as driven by the will (der Wille): a blind, insatiable, and irrational force underlying all existence. This concept challenges centuries of European rationalism, translating Eastern intuitive metaphysics into Western conceptual frameworks.

In many ways, Schopenhauer’s philosophy mirrors Buddhist sutras, emphasizing the inherent suffering of life (dukkha) and proposing liberation through the negation of desire. Amid the age of progress and rationality, his approach offered a radically different perspective: freedom is found in restraint, in taming desire, and in embracing the fundamental pain of existence.

In contrast to Hegel’s temple of reason, Schopenhauer places Buddha’s silent serenity, creating a counter-narrative that undercuts Western myths of unending progress.

Nietzsche: The Revolutionary Student

Nietzsche, however, is not merely a disciple of Schopenhauer; he is a polemicist who both inherits and transforms his teacher’s philosophy.

Nietzsche adopts Schopenhauer’s concept of will but radically reinterprets it as the will to power. While Schopenhauer sought to escape suffering by denying desire, Nietzsche embraces suffering as an essential and productive force. Life’s weight, Nietzsche argues, is not a burden to escape but a rhythm to dance with.

Central to Nietzsche’s philosophy is amor fati, the love of one’s fate. His concept of the eternal recurrence superficially echoes Eastern cyclical notions of time, yet in Nietzsche, it represents the joyful affirmation of life—to embrace the same existence repeatedly with vigor and acceptance.

Eastern Concepts in Western Philosophy

Through this intellectual lineage, concepts imported from the East gain new expression in Nietzsche’s thought, challenging the notion that Western philosophy is self-contained.

Philosophy’s history is often portrayed as a story confined to a single continent, but in reality, it is a transcontinental tapestry, woven from invisible threads and distant echoes. The “operating system” of Eastern metaphysics carried by Schopenhauer is applied in revolutionary ways by Nietzsche, demonstrating that human thought is a hybrid, evolving, and shared inheritance, rather than the property of any single civilization.

Thus, to understand Nietzsche fully, one must revisit Schopenhauer; to understand Schopenhauer, one must engage with the Upanishads. The history of philosophy is not just the tale of Europe’s internal dynamics but a record of humanity’s collective search, shaped by the interaction of multiple civilizations.

Key Lessons from This Connection

- Philosophy Is Not Geographically Isolated: Western ideas are not purely European; they are influenced by subtle, enduring echoes of Eastern thought.

- Suffering as a Philosophical Tool: While Schopenhauer proposes resignation from suffering, Nietzsche redefines suffering as a force for growth and creativity.

- Eastern Wisdom in Western Disguise: Concepts like Brahman, Maya, and Samsara are reinterpreted in European metaphysics, showing that ancient Eastern insights continue to inform modern philosophy.

- Life Affirmation Over Escape: Nietzsche’s call to embrace life, with all its contradictions, finds roots in Eastern philosophical traditions but blossoms in a distinctly Western voice.

Conclusion

The philosophical link between Nietzsche and the Upanishads, via Schopenhauer, reveals a hidden current in Western thought. It shows that the most radical ideas of Europe often have silent but enduring Eastern origins. This insight reshapes our understanding of intellectual history, reminding us that philosophy is a shared human endeavor, transcending geographical and cultural boundaries.

In exploring this connection, we not only gain a deeper appreciation of Nietzsche’s philosophy but also recognize the interwoven nature of global wisdom. True philosophical insight often lies in tracing these hidden threads, and the journey from the Upanishads to Schopenhauer to Nietzsche exemplifies the power of cross-cultural exchange in shaping thought.