Thrinaxodon hearing may have been far more advanced than scientists once believed, according to new biomechanical research that reshapes our understanding of early animal evolution. Long before dinosaurs dominated the land, this small prehistoric predator possessed the ability to detect faint sounds—possibly as soft as a whisper—giving it a survival advantage in a harsh, post-extinction world.

The discovery places the origins of mammal-style hearing millions of years earlier than previously assumed and suggests that key sensory adaptations began forming soon after one of the most devastating mass extinctions in Earth’s history.

A Small Predator From a World Rebuilding After Extinction

Thrinaxodon lived during the Early Triassic period, roughly 250 million years ago, a time when life on Earth was recovering from the Permian–Triassic mass extinction. Often called the “Great Dying,” this event wiped out an estimated 90 percent of marine species and around 70 percent of terrestrial vertebrates.

In this unstable environment, survival depended on adaptability. Thrinaxodon, a small carnivorous cynodont, stood out because it displayed a unique mix of reptilian and mammalian traits. Its body size was modest, but its anatomy hinted at evolutionary experimentation—especially in the skull and jaw.

For decades, paleontologists suspected that these features might relate to early hearing capabilities. Until recently, however, there was no concrete biomechanical evidence to support that idea.

Why Thrinaxodon Hearing Matters to Evolutionary Science

A Missing Link Between Reptiles and Mammals

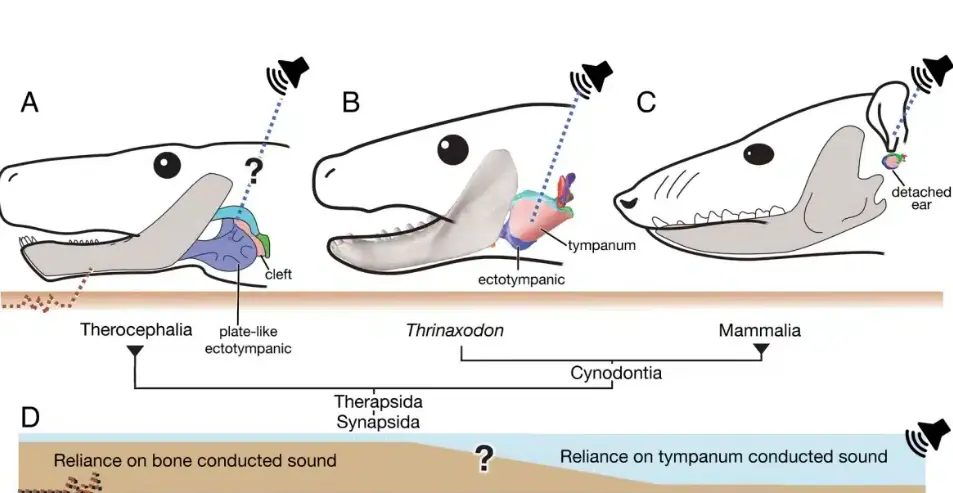

Cynodonts like Thrinaxodon occupy a crucial position in the evolutionary tree. They are not mammals, but they are closer to mammals than reptiles. Understanding how they sensed their environment helps scientists trace the gradual emergence of mammalian traits.

Hearing is particularly important because modern mammals rely on a specialized middle ear with three detached bones—the malleus, incus, and stapes. Reptiles, by contrast, depend largely on bone conduction, where vibrations travel through the jaw.

Thrinaxodon appears to sit between these two systems.

New Study Uses Modern Technology on Ancient Fossils

Advanced CT Scans and Digital Simulations

The new findings come from a study led by researchers at the University of Chicago, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The team revisited fossil skulls of Thrinaxodon using high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scans.

These scans allowed scientists to build precise 3D digital models of the animal’s skull and jaw. From there, they used advanced simulation software—tools more commonly associated with aerospace engineering and structural design—to test how sound vibrations would move through the bones.

This approach marked a major breakthrough. Rather than relying on anatomical speculation alone, researchers could now measure how the fossil structure would physically respond to sound.

Evidence for Early Tympanic Hearing

A Jaw Bone That Acts Like an Eardrum Support

One of the most important findings centers on a hook-shaped bone structure in Thrinaxodon’s jaw. In 1975, anatomist Edgar Allin proposed that this feature might have supported a primitive eardrum. At the time, the idea could not be tested.

Modern simulations finally made that test possible.

By modeling how the skull vibrated under different sound frequencies, researchers discovered that Thrinaxodon could transmit sound in a way that goes beyond simple bone conduction. This suggests a form of early tympanic hearing, even though its middle ear bones were still attached to the jaw.

How Well Could Thrinaxodon Hear?

Surprisingly Sensitive to Quiet Sounds

The simulations revealed that Thrinaxodon could detect sound frequencies ranging from 38 to 1,243 hertz, with peak sensitivity near 1,000 hertz. Most strikingly, the animal could likely detect sounds at around 28 decibels, roughly equivalent to a human whisper.

While this range is far narrower than that of modern humans—who typically hear from 20 to 20,000 hertz—it represents a major evolutionary leap. Compared to animals relying only on bone conduction, Thrinaxodon would have been far better at detecting subtle environmental sounds.

Why Hearing Was a Major Survival Advantage

Life in a Dangerous Post-Extinction World

In the Early Triassic, ecosystems were unstable and unpredictable. Predators and prey alike faced intense competition for limited resources. In such conditions, enhanced hearing could mean the difference between life and death.

Improved auditory sensitivity would have helped Thrinaxodon:

- Detect approaching predators

- Locate prey hidden in vegetation or burrows

- Communicate or respond to environmental cues

- Navigate low-light or underground environments

Some fossil evidence even suggests that Thrinaxodon may have lived in burrows, where sound detection would be especially valuable.

Thrinaxodon Hearing and the Origin of Mammalian Ears

Challenging Long-Held Assumptions

For much of the past century, scientists believed that mammalian hearing emerged relatively late, only after middle ear bones fully separated from the jaw. This new research challenges that timeline.

The findings indicate that the functional shift toward sound-based vibration detection began earlier, before the anatomical separation was complete. In other words, hearing evolved gradually, not suddenly.

As evolutionary scientist Alec Wilken explained, researchers were finally able to apply strong biomechanical tests to a problem that had remained unsolved for decades.

Confirming a Theory More Than 40 Years Old

Technology Catches Up With Hypothesis

Edgar Allin’s original idea lingered for over 40 years without definitive proof. The new study provides the first physical, testable evidence supporting his hypothesis.

According to Wilken’s advisor, paleontologist Zhe-Xi Luo, the simulations demonstrate that vibration through sound—not just bone—was the primary hearing mechanism for Thrinaxodon.

This confirmation reshapes how scientists understand the evolutionary pathway from reptile-like ancestors to modern mammals.

A Broader Impact on Paleontology

Rethinking Sensory Evolution

The implications of this research extend far beyond a single species. If Thrinaxodon had early tympanic hearing, other cynodonts may have shared similar abilities.

This opens new avenues of research into:

- The evolution of sensory systems after mass extinctions

- How environmental pressures accelerate anatomical innovation

- The origins of mammalian behaviors linked to hearing

It also demonstrates the power of modern digital tools to unlock secrets hidden in fossils for centuries.

Conclusion: A Quiet Revolution in Deep Time

Thrinaxodon hearing represents a critical step in the long evolutionary journey toward mammalian senses. Long before dinosaurs ruled the land, this small predator could already perceive the world in ways that foreshadow modern mammals.

The study shows that evolution often works in subtle stages, building complex systems piece by piece. Sometimes, the clues are not in dramatic new fossils, but in familiar bones viewed through new technology.